The Real Stalin Series Part 10: The Famine of 1932

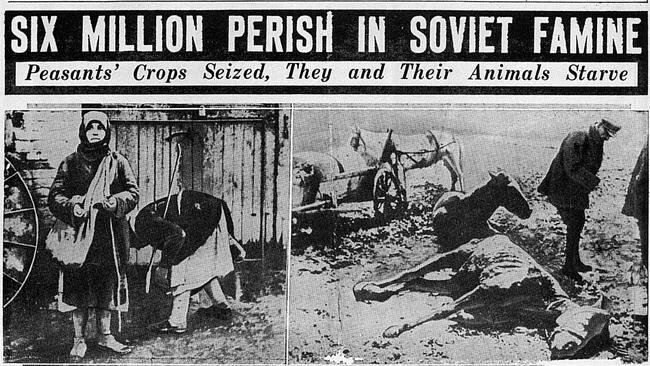

Front page of the Chicago American newspaper in 1935

FAMINE DID NOT OCCUR

For two years farming was dislocated, not, as often claimed, by Moscow’s enforcement of collectivization but by the fact that local people eager to be first at the promised tractors, organized collective farms three times as fast as the plan called for, setting up large-scale farming without machines even without bookkeepers. In 1932-33 the whole land went hungry; all food everywhere was rigidly rationed. (It has been often called a famine which killed millions of people, but I visited the hungriest parts of the country and while I found a wide-spread suffering, I did not find, either in individual villages or in the total Soviet census, evidence of the serious depopulation which famine implies.)

Strong, Anna L. The Soviets Expected It. New York, New York: The Dial press, 1941, p. 69

As far back as late August, 1933, the New Republic declared:

“… the present harvest is undoubtedly the best in many years–some peasants report a heavier yield of grain than any of their forefathers had known”since 1834. Grain deliveries to the government are proceeding at a very satisfactory rate and the price of bread has fallen sharply in the industrial towns of the Ukraine. In view these facts, the appeal of the Cardinal Archbishop [Innitzer] of Vienna for assistance for Russian famine victims seems to be a political maneuver against the Soviets.”

And, contrary to wild stories told by Ukrainian Nationalist exiles about “Russians” eating plentifully while deliberately starving “millions” of Ukrainians to death, the New Republic notes that while bread prices in Ukraine were falling, “bread prices in Moscow have risen.”…

It is a matter of some significance that Cardinal Innitzer’s allegations of famine-genocide were widely promoted throughout the 1930s, not only by Hitler’s chief propagandist Goebbels, but also by American Fascists as well. It will be recalled that Hearst kicked off his famine campaign with a radio broadcast based mainly on material from Cardinal Innitzer’s “aid committee.” In Organized Anti-Semitism in America, the 1941 book exposing Nazi groups and activities in the pre-war United States, Donald Strong notes that American fascist leader Father Coughlin used Nazi propaganda material extensively. This included Nazi charges of “atrocities by Jew Communists” and verbatim portions of a Goebbels speech referring to Innitzer’s “appeal of July 1934, that millions of people were dying of hunger throughout the Soviet Union.”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 49-51

…Sir John Maynard, a former high school… official in the Indian government was a renowned expert on famines and relief measures. On the basis of his experience in Ukraine, he stated that the idea of 3 or 4 million dead “has passed into legend. Any suggestion of a calamity comparable with the famine of 1921-1922 is, in the opinion of the present writer, who traveled through Ukraine and North Caucasus in June and July 1933, unfounded.” Even as conservative a scholar as Warren Walsh wrote in defense of Maynard, his “professional competence and personal integrity were beyond reasonable challenge.”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 52

Cold War confrontation, rather than historical truth and understanding, has motivated and characterized the famine-genocide campaign. Elements of fraud, anti-semitism, degenerate Nationalism, fascism, and pseudo- scholarship revealed in this critical examination of certain key evidence presented in the campaign…and historical background of the campaign’s promoters underline this conclusion.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 133

QUESTION: Is it true that during 1932-33 several million people were allowed to starve to death in the Ukraine and North Caucasus because they were politically hostile to the Soviets?

ANSWER: Not true. I visited several places in those regions during that period. There was a serious grain shortage in the 1932 harvest due chiefly to inefficiencies of the organizational period of the new large-scale mechanized farming among peasants unaccustomed to machines. To this was added sabotage by dispossessed kulaks, the leaving of the farms by 11 million workers who went to new industries, the cumulative effect of the world crisis in depressing the value of Soviet farm exports, and a drought in five basic grain regions in 1931. The harvest of 1932 was better than that of 1931 but was not all gathered; on account of overoptimistic promises from rural districts, Moscow discovered the actual situation only in December when a considerable amount of grain was under snow.

Strong, Anna Louise. “Searching Out the Soviets.” New Republic: August 7, 1935, p. 356

Opposing the tendency of many Communists to blame the peasants, Stalin said: “We Communists are to blame”–for not foreseeing and preventing the difficulties. Several organizational measures were at once put into action to meet the immediate emergency and prevent its reoccurrence. Firm pressure on defaulting farms to make good the contracts they had made to sell 1/4 their crop to the state in return for machines the state had given them (the means of production contributed by the state was more than all the peasants’ previous means) was combined with appeals to loyal, efficient farms to increase their deliveries voluntarily. Saboteurs who destroyed grain or buried it in the earth were punished. The resultant grain reserves in state hands were rationed to bring the country through the shortage with a minimum loss of productive efficiency. The whole country went on a decreased diet, which affected most seriously those farms that had failed to harvest their grain. Even these, however, were given state food and seed loans for sowing.

Simultaneously, a nationwide campaign was launched to organize the farms efficiently; 20,000 of the country’s best experts in all fields were sent as permanent organizers to the rural districts. The campaign was fully successful and resulted in a 1933 grain crop nearly 10 million tons larger than was ever gathered from the same territory before.

QUESTION: Is there a chance of another famine this year, as Cardinal Innitzer asserts?

ANSWER: Everyone in the Soviet Union to whom I mentioned this question just laughs.

Reasons for the laughter are:

Two bumper crops in 1933 and 1934.

A billion bushels of grain in state hands, enough to feed the cities and non-grain farmers for two years.

A grain surplus in farmers’ hands that has sufficed to increase calves 94% and pigs 118 percent in a single year.

The abolition of bread rationing because of surplus in grain.

The abolition of nearly half a billion rubles of peasant debts incurred for equipment during the organizing of collective farms–this as the result of an actual budget surplus in the government.

Tales of continued famine are Nazi propaganda on which to base a future invasion of the Ukraine [which did occur by the way].

Strong, Anna Louise. “Searching Out the Soviets.” New Republic: August 7, 1935, p. 357

DURANTY SEES NO FAMINE IN 1933

Kharkov, September 1933–I have just completed a 200 mile auto trip through the heart of the Ukraine and can say positively that the harvest is splendid and all talk of famine now is ridiculous…. The population, from the babies to the old folks, looks healthy and well nourished.

Duranty, Walter. Duranty Reports Russia. New York: The Viking Press, 1934, p. 318

STALIN’S VIEW OF CAUSE OF UKRAINIAN CROP FAILURES

[Footnote] In Stalin’s view, Ukrainian crop failures were caused by enemy resistance and by the poor leadership of Ukrainian officials.

Naumov, Lih, and Khlevniuk, Eds. Stalin’s Letters to Molotov, 1925-1936. New Haven: Yale University Press, c1995, p. 230

COLLECTIVE HARVESTS WERE NOT GOOD PRIOR TO 1933

One harvest was not enough to stabilize collectivization. In 1930, it was put over by poorly organized, ill-equipped peasants through force of desire. In the next two years, the difficulties of organization caught up with them. Where to find good managers? Bookkeepers? Men to handle machines? In 1931, the harvest fell off from drought in five basic grain areas. In 1932, the crop was better but poorly gathered. Farm presidents, unwilling to admit failure, claimed they were getting it in. When Moscow awoke to the situation, a large amount of grain lay under the snow.

Causes were many. Fourteen million small farms had been merged into 200,000 big ones, without experienced managers or enough machines. Eleven million workers had left the farms for the new industries. The backwardness of peasants, sabotage by kulaks, stupidities of officials, all played a part. By January 1933 it was clear that the country faced a serious food shortage, two years after it had victoriously “conquered wheat.”

Strong, Anna Louise. The Stalin Era. New York: Mainstream, 1956, p. 41

1933 HARVEST WAS THE BEST SINCE 1930 WHICH WAS A RECORD

From one end of the land to the other, there was shortage and hunger–and a general increase in mortality from this. But the hunger was distributed–nowhere was there the panic chaos that is implied by the word “famine.”

The conquest of bread was achieved that summer, a victory snatched from a great disaster. The 1933 harvest surpassed that of 1930, which till then had held the record. This time, the new record was made not by a burst of half-organized enthusiasm, but by growing efficiency and permanent organization.

Victory was consolidated the following year by the great fight the collective farmers made against a drought that affected all the southern half of Europe…. In each area where winter wheat failed, scientists determined what second crops were best; these were publicized and the government shot in the seed by fast freight. This nationwide cooperation beat the 1934 drought, securing a total crop for the USSR equal to the all-time high of 1933. Even in the worst regions, most farms came through with food for man and beast with strengthened organization.

Strong, Anna Louise. The Stalin Era. New York: Mainstream, 1956, p. 44-45

FAMINE WAS NOT CAUSED BY THE COMMUNIST LEADERSHIP

CHUEV: Among writers, some say the famine of 1933 was deliberately organized by Stalin and the whole of your leadership.

MOLOTOV: Enemies of communism say that! They are enemies of communism! People who are not politically aware, who are politically blind.

…If life does not improve, that’s not socialism. But even if the life of the people improves year to year over a long period but the foundations of socialism are not strengthened, a crack-up will be inevitable.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 243

This destruction of the productive forces had, of course, disastrous consequences: in 1932, there was a great famine, caused in part by the sabotage and destruction done by the kulaks. But anti-Communists blame Stalin and the `forced collectivization’ for the deaths caused by the criminal actions of the kulaks.

Martens, Ludo. Another View of Stalin. Antwerp, Belgium: EPO, Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27 2600, p. 79 [p. 66 on the NET]

In 1931 and 1932, the Soviet Union was in the depth of the crisis, due to socio-economic upheavals, to desperate kulak resistance, to the little support that could be given to peasants in these crucial years of industrial investment, to the slow introduction of machines and to drought.

Charles Bettelheim. L’Economie soviEtique (Paris: ƒditions Recueil Sirey, 1950), p. 82

Martens, Ludo. Another View of Stalin. Antwerp, Belgium: EPO, Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27 2600, p. 93 [p. 78 on the NET]

Recent evidence has indicated that part of the cause of the famine was an exceptionally low harvest in 1932, much lower than incorrect Soviet methods of calculation had suggested. The documents included here or published elsewhere do not yet support the claim that the famine was deliberately produced by confiscating the harvest, or that it was directed especially against the peasants of the Ukraine.

Koenker and Bachman, Eds. Revelations from the Russian Archives. Washington: Library of Congress, 1997, p. 401

In view of the importance of grain stocks to understanding the famine, we have searched Russian archives for evidence of Soviet planned and actual grain stocks in the early 1930s. Our main sources were the Politburo protocols, including the (“special files,” the highest secrecy level), and the papers of the agricultural collections committee Komzag, of the committee on commodity funds, and of Sovnarkom. The Sovnarkom records include telegrams and correspondence of Kuibyshev, who was head of Gosplan, head of Komzag and the committee on reserves, and one of the deputy chairs of Komzag at that time. We have not obtained access to the Politburo working papers in the Presidential Archive, to the files of the committee on reserves or to the relevant files in military archives. But we have found enough information to be confident that this very a high figure for grain stocks is wrong and that Stalin did not have under his control huge amounts of grain, which could easily have been used to eliminate the famine.

Stalin, Grain Stocks and the Famine of 1932-1933 by R. W. Davies, M. B. Tauger, S.G. Wheatcroft.Slavic Review, Volume 54, Issue 3 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 642-657.

This is in response to Ms. Chernihivaka’s note about the book of German letters and the reference to what she termed the “Ukrainian Famine” of the early 1930s.

I would just like to point out that I and a number of other scholars have shown conclusively that the famine of 1931-1933 was by no means limited to Ukraine, was not a “man-made” or artificial famine in the sense that she and other devotees of the Ukrainian famine argument assert, and was not a genocide in any conventional sense of the term. We have likewise shown that Mr. Conquest’s book on the famine is replete with errors and inconsistencies and does not deserve to be considered a classic, but rather another expression of the Cold War.

I would recommend to Ms. Chernihivaka the following publications regarding the 1931-1933 famine and some other famines as well. I will begin with my own because I believe that these most directly relate to her question. “The 1932 Harvest and the Soviet Famine of 1932-1933,” and the “Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931-1933.” These two articles show that the famine resulted directly from a famine harvest, a harvest that was much smaller than officially acknowledged, that this small harvest was in turn, the result of a complex of natural disasters that [with one small exception] no previous scholars have ever discussed or even mentioned. The footnotes in the Carl Beck paper contain extensive citations from primary sources as well as Western and Soviet secondary sources, among others by Penner, Wheatcroft and Davies that further substantiate these points, and I urge interested readers to examine these works as well.

Ukrainian Famine by Mark Tauger. E-mail sent on April 16, 2002

I am not a specialist on the Ukrainian famine but I am familiar with the recent research by several scholars on the matter, and think rather a lot of the deep and broad research that Mark Tauger has conducted over many years.

That familiarity leads me to believe that there are no simple answers to this. A “man-made” famine is not the same as a deliberate or “terror-famine”. A famine originally caused by crop failure and aggravated by poor policies is “man aggravated” but only partially “man-made”. Why in this field do we always insist on absolutes, especially categorical, binary and polemical ones? True/false. Good/evil. Crop failure/Man made.

Many questions have ambiguous answers.

1. Why was the Ukraine sealed off by the Soviet authorities?

Not necessarily to punish Ukrainians. It was also done to prevent starving people from flocking into non-famine areas, putting pressure on scarce food supplies there, and thereby turning a regional disaster into a universal one. This was also the original reason for the internal passport system, which was adopted in the first instance to prevent the movement of hungry and desperate people and, with them, the spread of famine.

2. Why were foreign journalists, even Stalin apologists like Duranty, refused access to the famine areas?

For the same reason that US journalists are no longer allowed into US combat zones (Gulf War, Afghanistan) since Vietnam. No regime is anxious to take the chance on bad press if they can control the situation otherwise.

3. Why was aid from other countries refused?

Obviously to deny the “imperialists” a chance to trumpet the failure of socialism. Certainly politics triumphed over humanitarianism. Moreover, in the growing paranoia of the times (and based on experience in the Civil War) the regime believed that spies came along with relief administration.

4. Why do I read and hear stories of families who tried to take supplies from other regions to help their extended families through the period having all foodstuffs confiscated as they crossed back into the famine regions?

The regime believed, reasonably I think, that speculators were trying to take advantage of the disaster by buying up food in non-famine (but nevertheless food-short) regions, moving it to Ukraine, and reselling it at a higher price. In true Bolshevik fashion, there was no nuanced approach to this, no distinguishing between families and speculators, and everybody was stopped. As with point 1 above, regimes facing famine typically try to contain the disaster geographically. This is not the same as intending to punish the victims.

5. If it was a harvest failure, why was the burden of that failure not simply shared across the Soviet Union?

It was. No region had a lot of food in 1932-33. Food was short and expensive everywhere. Everybody was hungry.

With the above suggestions, I do not mean to make excuses or apologies for the Stalinists. Their conduct in this was erratic, incompetent, and cruel and millions of people suffered unimaginably and died as a result. But it is too simple to explain everything with a “Bolsheviks were just evil people” explanation more suitable to children than scholars. It was more complex than that. Although the situation was aggravated in some ways by Bolshevik mistakes, their attempts to contain the famine, once it started, were not entirely stupid, nor were they necessarily gratuitously cruel. The Stalinists did, by the way, eventually cut grain exports and did, by the way, send food relief to Ukraine and other areas. It was too little too late, but there is no evidence (aside from constantly repeated assertions by some writers) that this was a deliberately inflicted “terror-famine.”

6. To deny the Jewish genocide quite rightly brings opprobrium. Surely to deny the terror famine of 1932-33 ought to provoke the same response.

This is a position that I personally find grotesque, insulting and at least shallow. Nobody is denying the famine or the huge scale of suffering, (as holocaust-deniers do), least of all Tauger and other researchers who have spent much of their careers trying to bring this tragedy to light and give us a factual account of it. Admittedly, what he and other scholars do is different from the work of journalists and polemicists who indiscriminately collect horror stories and layer them between repetitive statements about evil, piling it all up and calling it history. A factual, careful account of horror in no way makes it less horrible.

Ukrainian Famine by J. Arch Getty, E-mail sent on May 7, 2002

“There is no evidence, it [1932-33 famine] was intentionally directed against Ukrainians,” said Alexander Dallin of Stanford, the father of modern Sovietology. “That would be totally out of keeping with what we know–it makes no sense.”

“I absolutely reject it,” said Lynne Viola of SUNY– Binghamton, the first US historian to examine Moscow’s Central State archive on collectivization. “Why in god’s name, would this paranoid government consciously produce a famine when they were terrified of war [with Germany]?”

“He’s [Conquest] terrible at doing research,” said veteran Sovietologist Roberta Manning of Boston College. “He misuses sources, he twists everything.”

Which leaves us with a puzzle: Wouldn’t one or two or 3.5 million famine-related deaths be enough to make an anti-Stalinist argument? Why seize a wildly inflated figure that can’t possibly be supported? The answer tells much about the Ukrainian nationalist cause, and about those who abet it.

“They’re always looking to come up with a number bigger than 6 million,” observed Eli Rosenbaum, general counsel for the World Jewish Congress. “It makes the reader think: ‘My God, it’s worse than the Holocaust’.”

IN SEARCH OF A SOVIET HOLOCAUST [A 55 Year Old Famine Feeds the Right] by Jeff Coplon. Village Voice, New York City, January 12, 1988

The severity and geographical extent of the famine, the sharp decline in exports in 1932-1933, seed requirements, and the chaos in the Soviet Union in these years, all lead to the conclusion that even a complete cessation of exports would not have been enough to prevent famine. This situation makes it difficult to accept the interpretation of the famine as the result of the 1932 grain procurements and as a conscious act of genocide. The harvest of 1932 essentially made a famine inevitable.

…The data presented here provide a more precise measure of the consequences of collectivization and forced industrialization than has previously been available; if anything, these data show that the effects of those policies were worse than has been assumed. They also, however, indicate that the famine was real, the result of failure of economic policy, of the “revolution from above,” rather than of a “successful” nationality policy against the Ukrainians or other ethnic groups.

Tauger, Mark. “The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933,” Slavic Review, Volume 50, Issue 1 (Spring, 1991), 70-89.

Conquest replies,

Perhaps I might add that my own analyses and descriptions of the terror-famine first appeared in the USSR in Moscow in Russian journals such as Voprosy Istorii and Novyi Mir, and that the long chapter printed in the latter was specifically about the famine in Ukraine and hence relied importantly on Ukrainian sources.

Tauger replies,

Mr. Conquest does not deal with these arguments. He most nearly approaches in his assertion that in Ukraine and certain other areas “the entire crop was removed.” Since the regime procured 4.7 million tons of grain from Ukraine in 1932, much less than in any previous or subsequent year in the 1930’s, this would imply that the harvest in Ukraine was only on that order of magnitude or even less than my low estimate! Obviously this could not have been the case or the death toll in Ukraine would have been not four million or five million but more than 20 million because the entire rural population would have been left without grain….

I have yet to see any actual central directive ordering a blockade of Ukraine or the confiscation of food at the border. The sources available are still too incomplete to reach any conclusion about this.

Tauger, Mark & Robert Conquest. Slavic Review, Volume 51, Issue 1 (Spring, 1992), pp. 192-194.

Tauger replies further,

Robert Conquest’s second reply to my article does not settle in his favor the controversy between us over the causes of the 1933 famine. On his initial points, I noted that the famine was worse in Ukraine and Kuban than elsewhere, in great part because those regions’ harvests were much smaller than previously known. I rejected his evidence not because it was not “official” but because my research showed that it was incorrect.

Conquest cites the Stalin decree of January 1933 in an attempt to validate Ukrainian memoir accounts, to discredit the archival sources I cited and to prove that the Soviet leadership focused the famine on Ukraine and Kuban. The decree’s sanctions, however, do not match memoir accounts, none of which described peasants being returned to their villages by OGPU forces. The experiences described in those accounts instead reflect enforcement of a September 1932 secret OGPU directive ordering confiscations of grain and flour to stop illegal trade. Since this was applied throughout the country, the Ukrainian memoir accounts reflect general policy and not a focus on the Ukraine.

Several new studies confirm my point that hundreds of thousands of peasants fled famine not only in Ukraine and Kuban, but also in Siberia, the Urals, the Volga basin, and elsewhere in 1932-1933. Regional authorities tried to stop them and in November 1932 the Politburo began to prepare the passport system that soon imposed constraints on mobility nationwide. The January decree was thus one of several measures taken at this time to control labor mobility, in this case to retain labor in the grain regions lest the 1933 harvest be even worse. Its reference to northern regions suggests that it may even have been used to send peasants from those areas south to provide labor. Neither the decree itself nor the scale of its enforcement are sufficient to prove that the famine was artificially imposed on Ukraine.

…Ukrainian eyewitness accounts, on the other hand, are misleading because very few peasants from other regions had the opportunity to escape from the USSR after World War II. The Russian historian Kondrashin interviewed 617 famine survivors in the Volga region and explicitly refuted Conquest’s argument regarding the famine’s nationality focus. According to these eyewitnesses, the famine was most severe in wheat and rye regions, in other words, in part a result of the small harvest.

…Both Russian and western scholars such as Kondrashin…and Alec Nove…now acknowledge that the 1932 harvest was much smaller than assumed and was an important factor in the famine.

Tauger, Mark. Slavic Review, Volume 53, Issue 1 (Spring, 1994), pp. 318-320.

FIGURES ON FAMINE DEATHS ARE ABSURD AND FAR TOO HIGH

CHUEV: But nearly 12 million perished of hunger in 1933….

MOLOTOV: The figures have not been substantiated.

CHUEV: Not substantiated?

MOLOTOV: No, no, not at all. In those years I was out in the country on grain procurement trips. Those things couldn’t have just escaped me. They simply couldn’t. I twice traveled to the Ukraine. I visited Sychevo in the Urals and some places in Siberia. Of course I saw nothing of the kind there. Those allegations are absurd! Absurd! True, I did not have occasion to visit the Volga region….

No, these figures are an exaggeration, though such deaths had been reported of course in some places.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 243

What can one say about Conquest’s affirmation of 6,500,000 `massacred’ kulaks during the different phases of the collectivization? Only part of the 63,000 first category counter-revolutionaries were executed. The number of dead during deportations, largely due to famine and epidemics, was approximately 100,000. Between 1932 and 1940, we can estimate that 200,000 kulaks died in the colonies of natural causes. The executions and these deaths took place during the greatest class struggle that the Russian countryside ever saw, a struggle that radically transformed a backward and primitive countryside. In this giant upheaval, 120 million peasants were pulled out of the Middle Ages, of illiteracy and obscurantism. It was the reactionary forces, who wanted to maintain exploitation and degrading and inhuman work and living conditions, who received the blows. Repressing the bourgeoisie and the reactionaries was absolutely necessary for collectivization to take place: only collective labor made socialist mechanization possible, thereby allowing the peasant masses to lead a free, proud and educated life.

Through their hatred of socialism, Western intellectuals spread Conquest’s absurd lies about 6,500,000 `exterminated’ kulaks. They took up the defence of bourgeois democracy, of imperialist democracy.

Martens, Ludo. Another View of Stalin. Antwerp, Belgium: EPO, Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27 2600, p. 98 [p. 82 on the NET]

Lies about the collectivization have always been, for the bourgeoisie, powerful weapons in the psychological war against the Soviet Union.

Martens, Ludo. Another View of Stalin. Antwerp, Belgium: EPO, Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27 2600, p. 98 [p. 85 on the NET]

The borders of the Ukraine were not even the same in 1926 and 1939. The Kuban Cossaks, between 2 and 3 million people, were registered as Ukrainian in 1926, but were reclassified as Russian at the end of the twenties. This new classification explains by itself 25 to 40 per cent of the `victims of the famine-genocide’ calculated by Dushnyck–Mace.

Martens, Ludo. Another View of Stalin. Antwerp, Belgium: EPO, Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27 2600, p. 107 [p. 91 on the NET]

(Alec Nove)

Additionally, the figures on famine-related deaths cannot be precise, for “definitional” reasons…. Ukrainian statistics show a very large decline in births in 1933-34, which could be ascribed to a sharp rise in abortions and also to the non-reporting of births of those who died in infancy.

Getty and Manning. Stalinist Terror. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 269

Concerning the scale of the famine in 1932/33, we now have much better information on its chronology and regional coverage amongst the civilian registered population. The level of excess mortality registered by the civilian population was in the order of 3 to 4 million… which is still much lower than the figures claimed by Conquest and Rosefielde and Medvedev.

Getty and Manning. Stalinist Terror. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 290

The evidence presented to establish a case for deliberate genocide against Ukrainians during 1932-33, remains highly partisan, often deceitful, contradictory, and consequently highly suspect. The materials commonly used can almost invariably be traced to right-wing sources, anti-Communist “experts,” journalists or publications, as well as the highly partisan Ukrainian Nationalist political organizations. An important role in the thesis of genocide is assumed by the number of famine deaths–obviously it is difficult to allege genocide unless deaths are in the multi-millions. Here, the methodology of the famine-genocide theorists can at best be described as eclectic, unscientific; and the results, as politically manipulated guesstimates.

A “landmark study” in the numbers game is the article “The Soviet Famine of 1932-1934,” by Dana Dalrymple, published in Soviet Studies, January 1964. According to historian Daniel Stone, Dalrymple’s methodology consists of averaging “guesses by 20 Western journalists who visited the Soviet Union at the time, or spoke to Soviet emigres as much as two decades later. He averages the 20 accounts which range from a low of one million deaths (New York Herald Tribune, 1933) to a high of 10 million deaths (New York World Telegram, 1933.”

As Professor Stone of the University of Winnipeg suggests, Dalrymple’s method as no scientific validity; his “method” substitutes the art of newspaper clipping for the science of objective evidence gathering. This becomes apparent when one discovers the totally unacceptable use of fraudulent material built into the attempt to develop sensational mortality figures for the famine.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 45

While it is not possible to establish an exact number of casualties, we have seen that the guesstimates of famine-genocide writers have given a new meaning to the word hyperbole. Their claims have been shown to be extreme exaggerations fabricated to strengthen their political allegations of genocide.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 74

The scope of the hardships is chauvinistically restricted, distorted, and politically manipulated. Other nationalities who suffered–Russians, Turkmen, Kazaks, Caucasus groups– are usually ignored, or if mentioned at all are done so almost reluctantly in passing.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 99

Dr. Hans Blumenfeld, writing in response to Ukrainian Nationalist allegations of Ukrainian genocide, draws on personal experience in describing the people who came to town in search of food:

“They came not only from the Ukraine but in equal numbers from the Russian areas to our east. This disproves the “fact” of anti-Ukrainian genocide parallel to Hitler’s anti-semitic Holocaust. To anyone familiar with the Soviet Union’s desperate manpower shortage in those years, the notion that its leaders would deliberately reduce that scarce resource is absurd…. Up to the 1950s the most frequently quoted figure was 2 million [victims]. Only after it had been established that Hitler’s holocaust had claimed 6 million [Jewish] victims, did anti-Soviet propaganda feel it necessary to top that figure by substituting the fantastic figure of 7 to 10 million….”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 100

Had the 1941 population of Soviet Ukraine consisted of the remnants and survivors of a mass multi-million holocaust of a few years previous, or if they had perceived the 1932-1933 famine as genocide, deliberately aimed at Ukrainians, then doubtless fascism would have met a far different reception; Soviet Ukrainians would have been as reluctant to defend the USSR as Jewish survivors would have been to defend Nazi Germany.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 102

STALIN HAD TO EXPROPRIATE GRAIN IN THE WEST TO PREPARE FOR WAR WITH JAPAN

What happened was tragic for the Russian countryside. Orders were given in March, at the beginning of the spring sowing period in the Ukraine and North Caucasus and Lower Volga, that 2 million tons of grain must be collected within 30 days because the Army had to have it. It had to be collected, without argument, on pain of death. The orders about gasoline were hardly less peremptory. Here I don’t know the figures, but so many thousand tons of gasoline must be given to the Army. At a time when the collective farms were relying upon tractors to plow their fields.

That was the dreadful truth of the so-called “man-made famine,” of Russia’s “iron age,” when Stalin was accused of causing the deaths of four or 5 million peasants to gratify his own brutal determination that they should be socialized… or else. What a misconception! Compare it with the truth, that Japan was poised to strike and the Red Army must have reserves of food and gasoline.

… the fact remained that not only kulaks or recalcitrant peasants or middle peasants or doubtful peasants, but the collective farms themselves, were stripped of their grain for food, stripped of their grain for seed, at the season when they needed it most. The quota had to be reached, that was the Kremlin’s order. It was reached, but the bins were scraped too clean. Now indeed the Russian peasants, kulaks, and collectives, were engulfed in common woe. Their draft animals were dead, killed in an earlier phase of the struggle, and there was no gas for the tractors, and their last reserves of food and seed for the spring had been torn from them by the power of the Kremlin, which itself was driven by compulsion, that is by fear of Japan….

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 192

Their [peasants] living standards were so reduced that they fell easy prey to the malnutrition diseases–typhus, cholera, and scurvy, always endemic in Russia–and infected the urban populations….

Russia was wasted with misery, but the Red Army had restored its food reserves and its reserves of gasoline, and cloth and leather for uniforms and boots. And Japan did not attack. In August, 1932, the completion of the Dnieper Dam was celebrated in a way that echoed around the world. And Japan did not attack. Millions of Russian acres were deserted and untilled; millions of Russian peasants were begging for bread or dying. But Japan did not attack.

…The shortages of food and commodities in Russia were attributed, as Stalin had intended, to the tension of the Five-Year Plan, and all that Japanese spies could learn was that the Red Army awaited their attack without anxiety. Their spearhead, aimed at Outer Mongolia and Lake Baikal, were shifted, and her troops moved southwards into the Chinese province of Jehol, which they conquered easily and added to ” Manchukuo.” Stalin had won his game against terrific odds, but Russia had paid in lives as heavily as for war.

In the light of this and other subsequent knowledge, it is interesting for me to read my own dispatches from Moscow in the winter of 1932-33. I seem to have known what was going on, without in the least knowing why, that is without perceiving that Japan was the real key to the Soviet problem at that time, and that the first genuine improvement in the agrarian situation coincided almost to a day with the Japanese southward drive against Jehol.

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 193

It meant, to say it succinctly, that Stalin had won his bluff: Japan moved south, not north, and Russia could dare to use its best men….

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 195

WHAT FAMINE THERE WAS IN THE EARLY 30’S WAS CAUSED BY THE KULAKS

There was famine in the Ukraine in 1932-1933. But it was provoked mainly by the struggle to the bitter end that the Ukrainian far-right was leading against socialism and the collectivization of agriculture.

During the thirties, the far-right, linked with the Hitlerites, had already fully exploited the propaganda theme of `deliberately provoked famine to exterminate the Ukrainian people’. But after the Second World War, this propaganda was `adjusted’ with the main goal of covering up the barbaric crimes committed by German and Ukrainian Nazis, to protect fascism and to mobilise Western forces against Communism.

Martens, Ludo. Another View of Stalin. Antwerp, Belgium: EPO, Lange Pastoorstraat 25-27 2600, p. 113 [p. 96 on the NET]

The peasants passive resistance, the destruction of livestock, the complete disorganization of work in the kolkhozes, and the general ruin caused by continued dekulakization and deportations all lead in 1932-33 to a famine that surpassed even the famine of 1921-22 in its geographical extent and the number of its victims.

Nekrich and Heller. Utopia in Power. New York: Summit Books, c1986, p. 238

Was there or was there not a famine in the USSR in the years 1931 and 1932?

Those who think this a simple question to answer will probably already have made up their minds, in accordance with nearly all the statements by persons hostile to Soviet Communism, that there was, of course, a famine in the USSR; and they do not hesitate to state the mortality that it caused, in precise figures–unknown to any statistician–varying from three to six and even to 10 million deaths. On the other hand, a retired high official of the Government of India, speaking Russian, and well acquainted with czarist Russia, who had himself administered famine districts in India, and who visited in 1932 some of the localities in the USSR in which conditions were reported to be among the worst, informed the present writers at the time that he had found no evidence of there being or having been anything like what Indian officials would describe as a famine.

Footnote: Skepticism as to statistics of total deaths from starvation, in a territory extending to 1/6 of the Earth’s landmass, would anyhow be justified. But as to the USSR there seems no limit to the wildness of exaggeration. We quote the following interesting case related by Mr. Sherwood Eddy, an experienced American traveler in Russia: “Our party, consisting of about 20 persons, while passing through the villages heard rumors of the village of Gavrilovka, where all the men but one were said to have died of starvation. We went at once to investigate and track down this rumor. We divided into four parties, with four interpreters of our own choosing, and visited simultaneously the registry office of births and deaths, the village priest, the local soviet, the judge, the schoolmaster and every individual peasant we met. We found that out of 1100 families three individuals had died of typhus. They had immediately closed the school and the church, inoculated the entire population and stamped out the epidemic without developing another case. We could not discover a single death from hunger or starvation, though many had felt the bitter pinch of want. It was another instance of the ease with which wild rumors spread concerning Russia.”

Without expecting to convince the prejudiced, we give, for what it may be deemed worth, the conclusion to which our visits in 1932 and 1934, and subsequent examination of the available evidence, now lead us. That in each of the years 1931 and 1932 there was a partial failure of crops in various parts of the huge area of the USSR is undoubtedly true. That is true also of British India and of the United States. It has been true also of the USSR, and of every other country at all comparable in size, in each successive year of the present century. In countries of such vast extent, having every kind of climate, there is always a partial failure of crops somewhere. How extensive and how serious was this partial failure of crops in the USSR of 1931 and 1932 it is impossible to ascertain with any assurance. On the other hand, it has been asserted, by people who have seldom had any opportunity of going to the suffering districts, that throughout huge provinces there ensued a total absence of foodstuffs, so that (as in 1891 and 1921) literally several millions of people died of starvation. On the other hand, soviet officials on the spot, in one district after another, informed the present writers that, whilst there was shortage and hunger, there was, at no time, a total lack of bread, though its quality was impaired by using other ingredients than wheaten flower; and that any increase in the death-rate, due to diseases accompanying defective nutrition, occurred only in a relatively small number of villages. What may carry more weight than this official testimony was that of various resident British and American journalists, who traveled during 1933 and 1934 through the districts reputed to have been the worst sufferers, and who declared to the present writers that they had found no reason to suppose that the trouble had been more serious than was officially represented. Our own impression, after considering all the available evidence, is that the partial failure of crops certainly extended to only a fraction of the USSR; possibly to no more, than 1/10 of the geographical area. We think it plain that this partial failure was not in itself sufficiently serious to cause actual starvation, except possibly, in the worst districts, relatively small in extent. Any estimate of the total number of deaths in excess of the normal average, based on a total population supposed to have been subjected to famine conditions of 60 millions, which would mean half the entire rural population between the Baltic and the Pacific (as some have rashly asserted), or even 1/10 of such a population, appears to us to be fantastically excessive.

On the other hand, it seems to be proved that a considerable number of peasant households, both in the spring of 1932 and in that of 1933, found themselves unprovided with a sufficient store of cereal food, and specially short of fats. To these cases we shall return. But we are at once reminded that in countries like India and the USSR, in China, and even in the United States, in which there is no ubiquitous system of poor relief, a certain number of people–among these huge populations even many thousands–die each year of starvation, or of the diseases endemic under these conditions; and that whenever there is even a partial failure of crops this number will certainly be considerably increased. It cannot be supposed to have been otherwise in parts of the southern Ukraine, the Kuban district and Daghestan in the winters of 1931 and 1932.

But before we are warranted in describing this scarcity of food in particular households of particular districts as a “famine,” we must inquire how the scarcity came to exist. We notice among the evidence the fact that the scarcity was “patchy.” In one and the same locality, under weather conditions apparently similar if not identical, there are collective farms which have in these years reaped harvests of more than average excellence, whilst others, adjoining them on the north or on the south, have experienced conditions of distress, and may sometimes have known actual starvation. This is not to deny that there were whole districts in which drought or cold seriously reduced the yield. But there are clearly other cases, how many we cannot pretend to estimate, in which the harvest failures were caused, not by something in the sky, but by something in the collective farm itself. And we are soon put on the track of discovery. As we have already mentioned, we find a leading personage in the direction of the Ukrainian revolt actually claiming that “the opposition of the Ukrainian population caused the failure of the green-storing plan of 1931, and still more so, that of 1932.” He boasts of the success of the “passive resistance which aimed at a systematic frustration of the Bolshevik plans for the sowing and gathering of the harvest.” He tells us plainly that, owing to the efforts of himself and his friends, “whole tracks were left unsown,” and “in addition, when the crop was being gathered last year [1932], it happened that, in many areas, especially in the south, 20, 40 and even 50% was left in the fields, and was either not collected at all or was ruined in the threshing.”

So far as the Ukraine is concerned, it is clearly not Heaven which is principally to blame for the failure of crops, but the misguided members of many of the collective farms. What sort of “famine” is it that is due neither to the drought nor the rain, heat nor cold, rust nor fly, weeds nor locusts; but to a refusal of the agriculturists to sow (“whole tracks were left unsown”); and to gather up the wheat when it was cut (“even 50% was left in the fields”)?

Footnote: [“Ukrainia under Bolshevik Rule” by Isaac Mazepa, in Slavonic Review, January 3, 1934, pages 342-343.] One of the Ukrainian nationalists who was brought to trial is stated to have confessed to having received explicit instructions from the leaders of the movement abroad to the effect that “it is essential that, in spite of the good harvest (of 1930), the position of the peasantry should become worse. For this purpose it is necessary to persuade the members of the kolkhosi to harvest the grain before it has become ripe; to agitate among the kolkhosi members and to persuade them that, however hard they may work, their grain will be taken away from them by the State on one pretext or another; and to sabotage the proper calculation of the labor days put into harvesting by the members of the kolkhosi so that they may receive less than they are entitled to by their work” (Speech by Postyshev, secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, to plenum of the Central Committee, 1933).

Footnote: It can be definitely denied that the serious shortage of harvested grain in parts of southern Ukraine was due to climatic conditions. “In a number of southern regions, from 30 to 40% of the crop remained on the fields. This was not the result of the drought which was so severe in certain parts of Siberia, the Urals, in the Middle and Lower Volga regions that it reduced there the expected crops by about 50%. No act of God was involved in the Ukraine. The difficulties experienced in the sowing, harvesting, and grain collection campaign of 1931 were man-made” (“Collectivization of Agriculture in the Soviet Union,” by W. Ladejinsky, Political Science Quarterly, New York, June 1934, page 222).

The other district in which famine conditions are most persistently reported is that of Kuban, in the surrounding areas, chiefly inhabited by the Don Cossacks, who, as it is not irrelevant to remember, were the first to take up arms against the Bolshevik Government in 1918, and so begin the calamitous civil war. These Don Cossacks, as we have mentioned, had enjoyed special privileges under the tsars, the loss of which under the new regime has, even today, not been forgiven. Here there is evidence that whole groups of peasants, under hostile influences, got into such a state of apathy and despair, on being pressed into a new system of cooperative life which they could not understand and about which they heard all sorts of evil, that they ceased to care whether their fields were tilled or not, or what would happen to them in the winter if they produced no crop at all. Whatever the reason, there were, it seems, in the Kuban, as in the Ukraine, whole villages that sullenly abstained from sowing or harvesting, usually not completely, but on all but a minute fraction of their fields, so that, when the year ended, they had no stock of seed, and in many cases actually no grain on which to live. There are many other instances in which individual peasants made a practice, out of spite, of surreptitiously “barbering” the ripening wheat; that is, rubbing out the grain from the ear, or even cutting off the whole ear, and carrying off for individual hoarding this shameless theft of community property.

Unfortunately it was not only in such notoriously disaffected areas as the Ukraine and Kuban that these peculiar “failures of crops” occurred.

To any generally successful cultivation, he [Kaganovich] declared, “the anti-soviet elements of the village are offering fierce opposition. Economically ruined, but not yet having lost their influence entirely, the kulaks, former white officers, former priests, their sons, former ruling landlords and sugar-mill owners, former Cossacks and other anti-soviet elements of the bourgeois-nationalist and also of the social-revolutionary and Petlura-supporting intelligentsia settled in the villages, are trying in every way to corrupt the collective farms, are trying to foil the measures of the Party and the Government in the realm of farming, and for these ends are making use of the backwardness of part of the collective farm members against the interests of the socialized collective farm, against the interests of the collective farm peasantry.

Penetrating into collective farms as accountants, managers, warehouse keepers, brigadiers and so on, and frequently as leading workers on the boards of collective farms, the anti-soviet elements strive to organize sabotage, spoil machines, sow without the proper measures, steal collective farm goods, undermine labor discipline, organize the thieving of seed and secret granaries, sabotage grain collections–and sometimes they succeed in disorganizing kolkhosi.

However much we may discount such highly colored denunciations, we cannot avoid noticing how exactly the statements as to sabotage of the harvest, made on the one hand by the Soviet Government, and on the other by the nationalist leaders of the Ukrainian recalcitrants, corroborate each other. To quote again the Ukrainian leader, it was “the opposition of the Ukrainian population” that “caused the failure of the grain-storing plan of 1931, and still more so, that of 1932.” What on one side is made a matter for boasting is, on the other side, a ground for denunciation. Our own inference is merely that, whilst both sides probably exaggerate, the sabotage referred to actually took place, to a greater or less extent, in various parts of the USSR, in which collective farms had been established under pressure. The partial failure of the crops due to climatic conditions, which is to be annually expected in one locality or another, was thus aggravated, to a degree that we find no means of estimating, and rendered far more extensive in its area, not only by “barbering” the growing wheat, and stealing from the common stock, but also by deliberate failure to sow, failure to weed, failure to thresh, and failure to warehouse even all the grain that was threshed. But that is not what it is usually called a famine.

What the Soviet Government was faced with, from 1929 onward, was, in fact, not a famine but a widespread general strike of the peasantry, in resistance to the policy of collectivization, fomented and encouraged by the disloyal elements of the population, not without incitement from the exiles at Paris and Prague. Beginning with the calamitous slaughter of live-stock in many areas in 1929-1930, the recalcitrant peasants defeated, during the years 1931 and 1932, all the efforts of the Soviet Government to get the land adequately cultivated. It was in this way, much more than by the partial failure of the crops due to drought or cold, that was produced in an uncounted host of villages in many parts of the USSR a state of things in the winter of 1931-1932, and again in that of 1932-1933, in which many of the peasants found themselves with inadequate supplies of food. But this did not always lead to starvation. In innumerable cases, in which there was no actual lack of rubles, notably in the Ukraine, the men journeyed off to the nearest big market, and (as there was no deficiency in the country as a whole) returned after many days with the requisite sacks of flour. In other cases, especially among the independent peasantry, the destitute family itself moved away to the cities, in search of work at wages, leaving its rude dwelling empty and desolate, to be quoted by some incautious observer as proof of death by starvation. In an unknown number of other cases–as it seems, to be counted by the hundred thousand–the families were forcibly taken from the holding which they had failed to cultivate, and removed to distant places where they could be provided with work by which they could earn their substance.

The Soviet Government has been severely blamed for these deportations, which inevitably caused great hardships. The irresponsible criticism loses, however, much of its force by the inaccuracy with which the case is stated. It is, for instance, almost invariably taken for granted that the Soviet Government heartlessly refused to afford any relief to the starving districts. Very little investigation shows that relief was repeatedly afforded where there was reason to suppose that the shortage was not due to sabotage or deliberate failure to cultivate. There were, to begin with, extensive remissions of payments in-kind due to the government. But there was also a whole series of transfers of grain from the government stocks to villages found to be destitute, sometimes actually for consumption, and in other cases to replace the seed funds which had been used for food.

Footnote: Thus: “On February 17, 1932, almost six months before the harvesting of the new crop the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR and the Central Committee of the Communist Party, directed that the collective farms in the eastern part of the country, which had suffered from the drought, be loaned over 6 million quintals of grain for the establishment of both seed and food funds.”

(“Collectivization of Agriculture in the Soviet Union,” by W. Ladejinsky, Political Science Quarterly, New York, June 1934, page 229).

Webb, S. Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation. London, NY: Longmans, Green, 1947, p. 199-205

UKRAINIAN PARTY ORDERS CAUSES OF FAMINE BE EXPOSED AND PEOPLE BE HELPED

[Supplement to minutes of the Ukrainian Party Kiev bureau, Feb. 22, 1933, instructing that the famine be alleviated and that “all who have become completely disabled because of emaciation must be put back on their feet” by March 5]

… 10. In view of the continued attempts by our enemies to use these facts against the creation of collective farms, the Raion Party Committees are to conduct systematic clarification work bringing to light the real causes of the existing famine (abuses in the collective farms, laziness, decline in labor discipline, etc.).

Koenker and Bachman, Eds. Revelations from the Russian Archives. Washington: Library of Congress, 1997, p. 418

FAMINE LIES BEGAN WITH HEARST AGENT WALKER

In the fall of 1934, an American using the name Thomas Walker entered the Soviet Union. After tarrying less than a week in Moscow, he spent the remainder of his 13-day journey in transit to the Manchurian border, at which point he left the USSR never to return. This seemingly uneventful journey was the pretext for one of the greatest frauds ever perpetrated in the history of 20th century journalism.

Some four months later, on Feb. 18, 1935, a series of articles began in the Hearst press by Thomas Walker, “noted journalist, traveller and student of Russian affairs who has spent several years touring the Union of Soviet Russia.” The articles, appearing in the Chicago American and the New York Evening Journal for example, described in hair-raising prose a mammoth famine in the Ukraine which, it was alleged, had claimed “6 million” lives the previous year. Accompanying the stories were photographs portraying the devastation of the famine, for which it was claimed Walker had smuggled in a camera under the “most adverse and dangerous possible circumstances.”

In themselves, Walker’s stories in the Hearst press were not particularly outstanding examples of fraud concerning the Soviet Union. Nor were they the greatest masterpieces of yellow journalism ever produced by the right-wing corporate press. Lies and distortions had been written about the Soviet Union since the days of the October Revolution in 1917. The anti-Soviet press campaigns heated up in the late 20s and ’30s, directed by those, like Hearst, who wanted to keep the USSR out of the League of Nations and isolated in all respects.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 5

However, the Walker famine photographs are truly remarkable in that, having been exposed as utter hoaxes over fifty years ago, they continue to be used by Ukrainian nationalists and university propaganda institutes as evidence of alleged genocide. The extent of Walker’s fraud can only be measured by the magnitude and longevity of the lie they have been used to portray.

Horror stories about Russia were common in the Western press, particularly among papers and journalist of conservative or fascist orientation. For example, The London Daily Telegraph of November 28, 1930, printed an interview with a Frank Woodhead who had “just returned from Russia after a visit lasting seven months.” Woodhead reported witnessing bloody massacres that November, a slaughter which left “rows of ghastly corpses.”

Louis Fisher, an American writer for the New Republic and The Nation, who was in Moscow at the time of the alleged atrocities, discovered that not only had such events never occurred, but that Woodhead had left the country almost 8 months before the scenes he claimed to have witnessed. Fisher challenged Woodhead and the London Daily Telegraph on the matter; both responded with embarrassed silence.

When Thomas Walker’s articles appeared in the Hearst press, Fisher became suspicious–he had never heard of Walker and could find no one who had. The results of his investigation were published in the March 13, 1935 issue of The Nation:

“Mr. Walker, we are informed, ‘entered Russia last spring.’ that is the spring of 1934. He saw famine. He photographed its victims. He got heartrending, first-hand accounts of hunger’s ravages. Now famine in Russia is ‘hot’ news. Why did Mr. Hearst keep these sensational articles for ten months before printing them? My suspicions grew deeper….

I felt more and more sure that he was just another Woodhead, another absentee journalist. And so I consulted Soviet authorities who had official information from Moscow. Thomas Walker was in the Soviet Union once. He received a transit visa from the Soviet Consul in London on Sept. 29, 1934. He entered the USSR from Poland by train on October 12, 1934, (not the spring of 1934 as he says). He was in Moscow on the 13th. He remained in Moscow from Saturday, the 13th, to Thursday, the 18th, and then boarded a trans-Siberian train which brought him to the Soviet-Manchurian border on Oct. 25, 1934, his last day on Soviet territory. His train did not pass within several hundred miles of the black soil and Ukrainian districts which he ‘toured’ and ‘saw’ and ‘walked over’ and ‘photographed.’ It would have been physically impossible for Mr. Walker, in the five days between Oct. 13 and Oct. 18, to cover one-third of the points he ‘describes’ from personal experience. My hypothesis is that he stayed long enough in Moscow to gather from embittered foreigners the Ukrainian ‘local color’ he needed to give his articles the fake verisimilitude they possess.

Mr. Walker’s photographs could easily date back to the Volga famine in 1921. Many of them might have been taken outside the Soviet Union. They were taken at different seasons of the year…. One picture includes trees or shrubs with large leaves. Such leaves could not have grown by the ‘late sprang’ of Mr. Walker’s alleged visit. Other photographs show winter and early fall backgrounds. Here is the Journal of the 27th. A starving, bloated boy of 15 calmly poses naked for Mr. Walker. The next moment, in the same village, Mr. Walker photographs a man who is obviously suffering from the cold despite his sheepskin overcoat. The weather that sprang must have been as unreliable as Mr. Walker to allow nude poses one moment and require furs the next.

It would be easy to riddle Mr. Walker’s stories. They do not deserve the effort. The truth is that the Soviet harvest of 1933, including the Soviet Ukraine’s harvest, in contrast to that of 1932, was excellent; the grain-tax collections were moderate; and therefore conditions even remotely resembling those Mr. Walker portrays could not have arisen in the spring of 1934, and did not arise.”

Fisher challenged the motives of the Hearst press in hiring a fraud like Walker to concoct such fabrications:

“…Mr. Hearst, naturally does not object if his papers spoil Soviet-American relations and encourage foreign nations with hostile military designs upon the USSR. But his real target is the American radical movement. These Walker articles are part of Hearst’s anti-red campaign. He knows that the great economic progress registered by the Soviet Union since 1929, when the capitalist world dropped into depression, provides Left groups with spiritual encouragement and faith. Mr. Hearst wants to deprive them of that encouragement and faith by painting a picture of ruin and death in the USSR. The attempt is too transparent, and the hands are too unclean to succeed.”

In a post-script, Fisher added that a Lindsay Parrott had visited the Ukraine and had written that nowhere in any city or town he visited “did I meet any signs of the effects of the famine of which foreign correspondents take delight in writing.” Parrott, says Fisher, wrote of the “excellent harvest” in 1933; the progress, he declared, “is indisputable.” Fisher ends: “The Hearst organizations and the Nazis are beginning to work more and more closely together. But I have not noticed that the Hearst press printed Mr. Parrott’s stories about a prosperous Soviet Ukraine. Mr. Parrott is Mr. Hearst’s correspondent in Moscow.”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 7-8

WALKER ROUTINELY LIED AND WAS A CRIMINAL

In any event, it will be recalled that Walker was never in the Ukraine in 1932-1933.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 11

Not only were the photographs a fraud, the trip to Ukraine a fraud, and Hearst’s famine-genocide series a fraud, Thomas Walker himself was a fraud. Deported from England and arrested on his return to the United States just a few months after the Hearst series, it turned out that Thomas Walker was in fact escaped convict Robert Greene. The New York Times reported: “Robert Greene, a writer of syndicated articles about conditions in Ukraine, who was indicted last Friday by a Federal grand jury on a charge of passport fraud, pleaded guilty yesterday before Federal Judge Francis Caffey. The judge learned that Green was a fugitive from Colorado State Prison, where he escaped after having served two years of an 8-year term for forgery.”

Robert Greene, it was revealed, had run-up an impressive criminal record spanning three decades. His trail of crime led through five U.S. states and four European countries, and included convictions on charges of violating the Mann White Slave Act in Texas, forgery, and “marriage swindle.”

Evidence at Walker’s trial revealed that he had made a previous visit to the Soviet Union in 1930 under the name Thomas Burke. Having worked briefly for an engineering firm in the USSR, he was–by his own admission–expelled for attempting to smuggle a “a whiteguard” out of the country. A reporter covering the trial noted that Walker “admitted that the ‘famine’ pictures published with his series in the Hearst newspapers were fakes and they were not taken in Ukraine as advertised.”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 11

(Actually, one must recall, Walker never set foot in Ukraine, and entered the Russian Federation in the fall of 1934.)

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 59

Mace and his Harvard colleagues have the further audacity to state, in their introduction to Walker’s material: “American newspapermen… Thomas Walker… wrote plainspoken and graphic accounts of the Famine based on what he had witnessed in Ukraine in 1933.” Ignoring the fraudulent nature of the Walker series exposed over 50 years ago, the Harvard scholars conveniently backdate Walker’s stated 1934 trip to 1933….

Not only is this “scholarship” riddled with inaccuracies, exaggeration, distortion, and fraud, it resorts uncritically to Nazi sources without informing the reader of the spurious nature of the sources.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 61

HERRIOT TRAVELED THE UKRAINE AND SAID HE SAW NO FAMINE

It was following Hearst’s trip to Nazi Germany that the Hearst press began to promote the theme of “famine-genocide in Ukraine.” Prior to this, his papers had at times reflected a different perspective. For example, the October 1, 1934 Herald and Examiner, carried an article about the former French Premier, Herriot, who had recently returned from traveling around Ukraine. Herriot noted: “… the whole campaign on the subject of famine in the Ukraine is currently being waged. While wandering around the Ukraine, I saw nothing of the sort.”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 15

FAKE PHOTOS OF EARLY 20’S FAMINE WERE APPLIED TO EARLY 30’S

Indeed, a wide assortment of photos and documentary film footage was taken in Russia, Ukraine, Eastern Europe and Armenia during the period of World War I, the Russian Revolution, Civil War, and foreign intervention, events which contributed to the Russian famine of 1921-22. These photos–taken by journalists, relief agencies, medical workers, soldiers and individuals–were frequently published in the newspapers and brochures of the period. Such photos were the most likely source for the famine-genocide photographic “evidence”: they could be easily culled from archives, collections, and newspaper morgues and grafted onto accounts of the 1930s.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 31

Overall, the film’s [Harvest of Despair] producers, Nowytsky and Luhovy, have managed to slap together a patchwork of material. Film reviewer Leonard Klady noted that co-producer Luhovy “admits most of his income comes from editing feature films of dubious quality. He has a reputation as a good ‘doctor’–someone who’s brought in to salvage a movie which is deemed unreleasable by film exhibitors and distributors.” In Harvest of Despair it appears that the doctor delivered one of the great cinema miscarriages of all time. Objectivity and scientific presentation are sacrificed on the altar of Cold War psychological warfare.

According to the Winnipeg Free Press, Luhovy “personally viewed more than one million feet of historic stock footage to find roughly 20 minutes (720 feet) of appropriate material for the film.” This says less about his research than about the total lack of photographic evidence of famine-genocide.

Indeed, not one documented piece of evidence is presented in the film to back up the genocide thesis. Instead, in a montage of undocumented stills, the viewer is subjected to Walker/Ditloff forgeries; numerous scenes stolen from the bi-now familiar publications covering the 1921-1922 Russian famine, Ammende photos (with all their contradictions noted earlier); 1920s photos used in the Nazi organ Volkischer Beobachter in 1933. Certain Harvest of Despair photos can also be traced to Laubenheimer’s Nazi propaganda books, as well as to a Ukrainian-language publication published in Berlin in 1922.

Other scenes both borrow from the past and from the future. For example, footage of marching soldiers has Red Army men wearing uniforms from the days of the Russian Civil War. Footage of impoverished women cooking is also of Civil War vintage. Other scenes display peasant costumes from the Volga Russian area of the immediate post-World War 1 period, not Ukrainians in 1933. Footage of miners pulling coal sledges on their hands and knees is actually of Czarist-era origins. Scenes of peasants at meetings wearing peculiar tall peaked caps date from earlier periods; further, their clothing is not consistent with Ukrainian costume. Material filched from Soviet films of the 1920s can be identified, including sequences from Czar Hunger (1921-1922) and Arsenal (1929), and even from pre-revolutionary newsreels.

Flipping forward to the future, the film shows scenes of military manufacturing of tank models not produced until later in the 1930s. As well: “the episode of bread distribution in Nazi besieged Leningrad (taken from ‘The Siege of Leningrad,’ one film of the epic ‘An Unknown War’) was used by the authors of the videofraud as ‘filmed evidence’ of food shortage… in Ukraine in the 1930s.” And so on, and so on.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 78

It seems that like others before them, the producers of Harvest of Despair scrounged through the archives looking for bits and pieces of old war-and-starvation shots that might be spiced into the film to great subliminal effect–bound together with narrative and interspersed partisan interviews. As much has been admitted, as we will see.

In November 1986, Ukrainian Nationalists in alliance with right-wing school board officials, made an attempt to place their famine-genocide propaganda in the Toronto high school curriculum. Toward this end, a film showing of Harvest of Despair was arranged at the Education Center. Panelists advertised for the event included then vice-chairman of the Toronto Board Of Education Nola Crewe, Dr. Yury Boshyk, Research Fellow at Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute and Marco Carynnyk, writer and researcher associated with Harvest of Despair in its research stage.

Confronted by this author in the discussion portion of the meeting, that the stills and footage used in the film were fraudulent, the panelists were forced to admit openly that this author’s charges were true. Though reluctant to acknowledge the full extent of the fraud, deliberate deceit was confirmed. As the Toronto Star reported:

“Researcher Marco Carynnyk, who says he originated the idea of the film, says his concerns about questionable photographs were ignored. Carynnyk said that none of the archival film footage is of the Ukrainian famine and that very few photos from 1932-1933 appear that can be traced as authentic. A dramatic shot at the film’s end of an emaciated girl, which has also been used in the film’s promotional material, is not from the 1932-1933 famine, Carynnyk said.

“I made the point that this sort of inaccuracy cannot be allowed,” he said in an interview. “I was ignored.”

Perhaps this is why, to use the term of B.S. Onyschuk, vice-chairman of the Ukrainian Famine Research Committee, Carynnyk was “let go” from the film before its completion.

In light of the above, one wonders why Carynnyk waited several years before coming forward publicly with the truth, and even then only after a public challenge and exposure by this author.

In a quite incredible admission from an academic, Orest Subtelny, a history professor at York University, justified the use of frauds. Noting that there exist very few pictures of the 1933 famine, Subtelny defended the actions of the film’s producers: “You have to have visual impact. You want to show what children dying from a famine look like. Starving children are starving children.”

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 79

Dr. Ditloff, it will be recalled, was Director of the German government’s agricultural concession in the North Caucasus under an agreement between the German government and the Soviets. When Hitler took power in early 1933, Ditloff did not resign in protest. He remained as Director for the project’s duration, indicating that the Nazis did not consider him inimical to their interests. Following his return to Nazi Germany later that year, Ditloff gathered or fronted for a spurious assortment of famine photographs. These, as has been shown, included photos stolen from 1921-1922 famine sources. In addition, at least 25 of the Ditloff photos can be shown to have been released by the Nazis, many of which were passed to or picked up by various anti-Soviet and pro-fascist publishers abroad.

Some of Ditloff’s photos were published in the Nazi party organ Volkischer Beobachter (Aug. 18, 1933).

Whatever the actual mechanics of the distribution of the Ditloff-Walker photographs, their fraudulence is well-established. Those intent on propagating the famine-genocide myth for political/purposes have not hesitated to use these photographs repeatedly to this day–without adding a shred of authenticating evidence to this questionable material.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 34-35

NAZIS TRY TO BLAME SOVIET FOR MASS EXECUTIONS IN THE UKRAINE

Included in Volume 1 of The Black Deeds of the Kremlin is a special section devoted to Nationalist allegations of Soviet mass executions…in Vynnitsya. Unearthed in 1943 during the Nazi occupation, the graves were “examined” by a Nazi-appointed “Commission” and were featured in Nazi propaganda films….

Post-war testimony of German soldiers, however, exposes the unearthing of mass graves at Vynnitsya as a Nazi propaganda deception.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 37

According to Israel’s authoritative Yad Washem Studies, Oberleutnant Erwin Bingel testified that on Sept. 22, 1941, he witnessed the mass execution of Jews by the SS and Ukrainian militia. This included a slaughter carried out by Ukrainian auxiliaries in Vynnitsya Park, where Bingel witnessed “layer upon layer” of corpses buried. Returning to Vynnitsya later in the war, Bingel read of the experts brought in by the Nazis to examine the exhumed graves of “Soviet” execution victims in the same Park. Upon personal verification, Bingel concluded that the “discovery” had been staged for Nazi propaganda purposes and that the number of corpses he saw corresponded to those slaughtered by Ukrainian Fascists in 1941.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 40

NYT CORRESPONDENT DENNY SAYS HE SEES NO FAMINE IN THE UKRAINE

By all credible accounts, the crops of 1933 and 1934 were successful. As a tribute to this fact, very few, if any famine-genocide hustlers today support claims of a 1934 famine. However, both Ammende [Author in 1936 of the famine-genocide book entitled Human Life in Russia], and following him Dalrymple, seemed to have been determined to starve Ukraine to death in 1934 as well. In fact, Dalrymple’s Ammende source for the list of 20 is Ammende’s letter to the New York Times published on July 1, 1934 under the heading “Wide Starvation in Russia Feared.” In a follow-up letter the following month, Ammende wrote that people were dying on the streets of Kiev. Within days, New York Times correspondent Harold Denny cabled a refutation of Ammende’s allegations. Datelined August 23rd, 1934, Denny charged: “This statement certainly has no foundation…. Your correspondent was in Kiev for several days last July about the time people were supposed to be dying there, and neither in the city, nor in the surrounding countryside was their hunger.” Several weeks later, Denny reported: “Nowhere was famine found. Nowhere even the fear of it. There is food, including bread, in the local open markets. The peasants were smiling too, and generous with their foodstuffs. In short, there was no air of trouble or of impending trouble.”

Obviously, nobody had informed the peasants that they were supposed to be falling prostrate with hunger that year.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 50

Before departing Dalrymple’s list, let it be noted that a significant number of the sources have been shown to be either complete frauds, hearsay based on “foreign residents” (an interesting journalistic term) or hearsay altogether, former Nazis and Ukrainian collaborators, while at least three of the estimates are cited from the anti-Soviet campaigns of the neo-fascist Hearst–Scripps-Howard style press and another five from books published in the Cold War years of 1949-53, save one which was printed in Nazi Germany.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine, and Fascism. Toronto: Progress Books,1987, p. 51