The Real Stalin Series Part 3: The New Economic Policy (NEP)

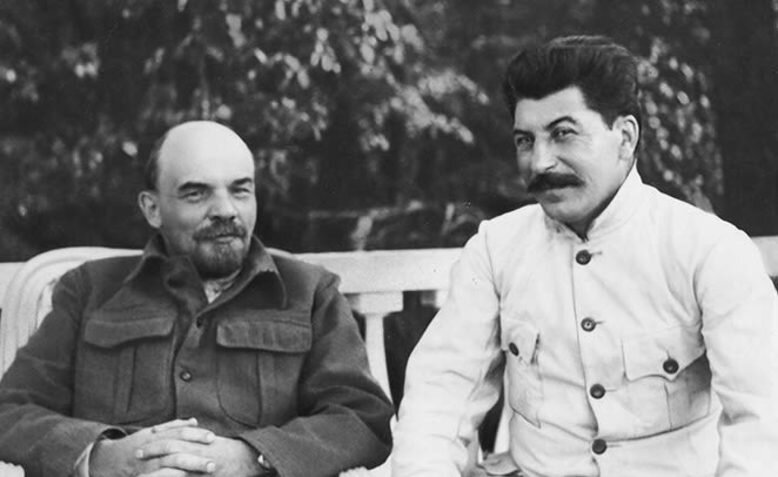

TROTSKY TRIED TO SUCCEED LENIN AND FAILED BADLY

Immediately after Lenin’s death, Trotsky made his open bid for power. At the Party Congress in May 1924 Trotsky demanded that he, and not Stalin, be recognized as Lenin’s successor. Against the advice of his own allies, he forced the question to a vote. The 748 Bolshevik delegates at the Congress voted unanimously to maintain Stalin as general secretary, and in condemnation of Trotsky’s struggle for personal power. So obvious was the popular repudiation of Trotsky that even Bucharin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev were compelled to side publicly with the majority and vote against him. Trotsky furiously assailed them for “betraying” him. But a few months later Trotsky and Zinoviev again joined forces and formed a “New Opposition.”

An actual secret Trotskyite army was in process of formation on Soviet soil.

Sayers and Kahn. The Great Conspiracy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1946, p. 199

Trotsky was in the Politburo, but in fact everyone had united around Stalin, including the right-wing–Bukharin and Rykov. We called ourselves “the majority” against Trotsky. He surely sensed, of course, this collusion against him. He had his supporters and we had ours. But he did not have many in the Politburo or in the Central Committee, only two or three. There was Shliapnikov from the Workers Opposition and Krestinsky from the Democratic Centralists.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 143

…The official history of the Communist Party suggests that Trotsky was emboldened by Lenin’s illness to make a deliberate bid for power as Lenin’s successor. This may be an exaggeration, although Trotsky must have known that Lenin was doomed, but it is significant that he mobilized a powerful group of critics to sign a document called the “Declaration of the Forty-six.” The declaration was a blow to the Central Committee, but Trotsky was rash enough to pursue his advantage by a letter which not only carried the attack further but established himself as leader of what was described by the Central Committee as an Opposition bloc. The word “opposition” or “factionalism” produced a reaction. The Central Committee retorted fiercely that Trotsky was not a Bolshevik at heart and never had been, that he and his “Forty-six” were voicing Menshevik heresies as they had done before, and that most of them had already been castigated by Lenin for subversive or mistaken ideas.

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 105

ZINOVIEV AND LENIN PROPOSE STALIN FOR GENERAL SEC.

He [Zinoviev] accordingly proposed Stalin for the post of General Secretary of the Central Committee of the party. Lenin agreed, and Stalin was appointed.

Basseches, Nikolaus. Stalin. London, New York: Staples Press, 1952, p. 91

Indeed, it had been Zinoviev who, after the Civil War, had proposed Stalin as General Secretary of the party.

Basseches, Nikolaus. Stalin. London, New York: Staples Press, 1952, p. 144

On Lenin’s motion, the Plenum of the Central Committee, on April 3, 1922, elected Stalin, Lenin’s faithful disciple and associate, General Secretary of the Central Committee, a post at which he has remained ever since.

Alexandrov, G. F. Joseph Stalin; a Short Biography. Moscow: FLPH, 1947, p. 74

But Lenin, after all, at the 10th Congress had prohibited factionalism.

And we voted with that note on Stalin in brackets. He became general secretary…. Lenin…made Stalin general secretary. Lenin was, of course, making preparations, for he sensed his ill health. Did he perhaps see in Stalin his successor? I think one can allow for that.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 105

CHUEV: At the office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, I was told that Lenin did not nominate Stalin to the post of general secretary. Rather, Kamenev did, and Lenin approved it….

MOLOTOV: Well, well. I know for sure that Lenin nominated him.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 166

In this connection it is interesting to note that the Congress ratified Lenin’s appointment a few weeks earlier of Stalin as General Secretary of the Party. This was a key position of authority and influence, and it is most significant that Lenin awarded it to Stalin, leader of the “underground” laborers in Russia’s vineyards during the pre-war period of repression, rather than to the more spectacular Trotsky or any of the Marxian purists among the “Western” exiles.

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 70

When in 1923 I learned that Lenin could not long survive and began to wonder about his successor, I remembered a conversation in my office in Moscow two years before. A Russian friend had said to me, “Stalin has been appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party.”

“What does that mean?” I replied.

“It means,” said the Russian impressively, “that he now becomes next to Lenin, because Lenin has given into his hands the manipulation of the Communist Party, which is the most important thing in Russia.”

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 165

On April 3, 1922, the plenum elected Stalin general secretary….

A Biographical Chronicle of Lenin’s life and work, published in recent years, gives the following account of April 3, 1922, based on materials from Party archives.

“…The plenum makes the decision to establish the position of general secretary with two Central Committee secretaries. Stalin is assigned to be general secretary; Molotov and Kuibyshev are the secretaries.”

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 67-68

[Footnote]: Trotsky and Medvedev attempt to absolve Lenin of responsibility for Stalin’s appointment as General Secretary, but there is persuasive evidence that Lenin had entrusted Stalin with party affairs during Lenin’s leave of absence and that he proposed him as General Secretary.

McNeal, Robert, Stalin: Man and Ruler. New York: New York University Press, 1988, p. 344

STALIN DID NOT PACK PARTY WITH HIS SUPPORTERS

It has often been stated, especially by Stalin’s opponents, that he busied himself at this time giving posts to his supporters throughout the party organization. This, of course, was not so. Stalin had spent most of the early years of the revolution at the fronts, and as yet had never come forward as a leader in any ideological current within Bolshevism: where could he have found all these personal supporters?….

Certainly no such army of supporters of Stalin had existed. On the other hand, he was the creator of the bureaucratic machinery of the party, and on the whole the members of the bureaucracy were loyal to its creator and controller. Only on the whole, for the later conflicts showed that very many of the party officials whose names he had put forward were opponents of his.

Basseches, Nikolaus. Stalin. London, New York: Staples Press, 1952, p. 95-96

…As General Secretary of the Party Central Committee, he [Stalin] held a strategically dominating position in matters of organization; and his opponents, especially the Trotskyists, charge that he used to the fullest extent the opportunities which this post afforded of packing the provincial and city Party committees with his own partisans. The Stalinites retort that these are slanderous accusations, put into circulation by disgruntled people who failed to capture control of the Party for their own ends. They point to the unanimous votes registered at Party Conferences and Congresses as proof that Stalin’s policies command the approbation of the solid masses of the Party members.

Chamberlin, William Henry. Soviet Russia. Boston: Little, Brown, 1930, p. 91

ZINOVIEV BACKED UP STALIN FOR GEN. SEC.

The most powerful man in the party was then Zinoviev, and he was in favor of Stalin; it was he who had proposed him for the party secretaryship. So Stalin remained secretary.

Basseches, Nikolaus. Stalin. London, New York: Staples Press, 1952, p. 109

Perhaps they signified their real thoughts when they unanimously confirmed the election to the important post of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, of Joseph Stalin, friend and close confidant of the absent president.

Cole, David M. Josef Stalin; Man of Steel. London, New York: Rich & Cowan, 1942, p. 59

When, at the April 1922 Plenum of the Central Committee, Kamenev proposed acceptance of Zinoviev’s idea of making Stalin general secretary of the Central Committee, Lenin–although he knew Stalin all too well–had no objection.

Bazhanov, Boris. Bazhanov and the Damnation of Stalin. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, c1990, p. 27

MEMBERS VOTED FOR STALIN BECAUSE THEY WANT HIM, NOT OUT OF FEAR

RUDZUTAK: Comrades, can one utter a greater slander against the members of the Central Committee, against the Old Bolsheviks, the majority of whom served years at hard labor? These, the finest people of the party, did not fear many years in prison and in exile, and now these revolutionaries, who devoted themselves to the victory of the revolution, these old revolutionary warriors, according to Smirnov, are afraid to vote against Comrade Stalin. Can be that they vote for Stalin from a fear for authority while, behind his back, they prepare–if anything comes up–to change the leadership? You are slandering the members of the party, you’re slandering the members of the Central Committee, and you are also slandering Comrade Stalin. We, as members of the Central Committee, vote for Stalin because he is ours….”

RUDZUTAK: “You won’t find a single instance where Stalin was not in the front rank during periods of the most active, most fierce battle for socialism and against the class enemy. You won’t find a single instance where Comrade Stalin has hesitated or retreated. That is why we are with him. Yes, he vigorously chops off that which is rotten, he chops off that which is slated for destruction. If he didn’t do this, he would not be a Leninist. He would not be a Communist fighter. In this lies his chief and finest and fundamental merit and quality as a leader-fighter who leads our party.”

Getty & Naumov, The Road to Terror. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, c1999, p. 93

PREOBRAZHENSKY WANTS STALIN DISMISSED AS GEN. SEC. BECAUSE HE HAS TOO MANY JOBS

Preobrazhensky was later among the opposition, a Trotskyist. He proposed that Stalin be dismissed from the position of general secretary on the grounds that he held too many offices. At the time Lenin strongly defended Stalin….”

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 113

At the Eighth Congress Stalin was re-elected to the Central Committee. Although the Central Committee was not very large then, a decision was made to establish a smaller direct body within it–a Political Bureau (Politburo), which would decide important political issues on a day-to-day basis. The first Politburo consisted of Lenin, Kamenev, Krestinsky, Stalin, and Trotsky. The candidate members were Bukharin, Kalinin, and Zinoviev. An Organizational Bureau (Orgburo) was also established for the first time to direct the ongoing organizational work of the party. It consisted of five members: Beloborodov, Krestinsky, Serebryakov, Stalin, and Stasova. A few days later a decree of the Central Executive Committee appointed Stalin peoples commissar of state control.

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 59

At the 11th Party Congress Preobrazhensky proposed that Stalin’s powers be somewhat curtailed. He said in his speech:

“Take Comrade Stalin, for example, a member of the Politburo who is, at the same time, peoples commissar of two commissariats. Is it conceivable that a person could be responsible for the work of two commissariats, and in addition work in the Politburo, the Orgburo, and a dozen Central Committee subcommissions?”

Lenin answered Preobrazhensky as follows:

“Preobrazhensky comes along and airily says that Stalin is involved in two different commissariats. Who among us has not sinned in this way? Which of us has not taken on several responsibilities at once? And how could we do otherwise? What can we do now to maintain the existing situation in the Commissariat of Nationalities, in order to sort out all the Turkestan, Caucasian, and other questions? After all, these are political questions! And these questions have to be answered. They are questions such as European states have occupied themselves with for hundreds of years, and only an insignificant portion of such problems have been solved in the democratic republics. We are working to resolve them and we need a man to whom representatives of any of our different nations can go and discuss their difficulties in full detail. Where are we to find such a person? I think that even Preobrazhensky would be unable to name another candidate besides Comrade Stalin.

The same thing applies to the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection. This is a vast business; but to be able to handle investigations we must have someone in charge who has authority. Otherwise we’ll get bogged down in petty intrigues.”

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 66

At the end of March 1919 Yelena Stasova was elected as chief secretary for the Central Committee. She encountered difficulties, and in November of the same year a Central Committee plenum elected Krestinsky to be second secretary of the Central Committee. In April 1920 a Secretariat consisting of three people–Krestinsky, Preobrazhensky, and Serebryakov–was elected. The leading figure in the Secretariat became Krestinsky, who also belonged to the Orgburo & Politburo. However, during the “trade union discussion,” all the Central Committee secretaries supported Trotsky’s or Bukharin’s platform and none of them were re-elected at the Central Committee plenum following the Tenth Party Congress. Instead Molotov, Yaroslavski, and Mikhailov were elected to the Secretariat. They were all members of the Orgburo as well.

Lenin, however, was displeased with the work of these party centers, accusing them of inadmissible red tape, delay, and bureaucratism. It was assumed, therefore, that the election of Stalin, whose organizational abilities and abrupt manner were well known in party circles, would bring order into the working bodies of the Central Committee.

The situation changed as Lenin’s illness grew worse, removing him more and more often from the administration of the country and direction of the party. Stalin was not only general secretary; he belonged to the Orgburo, the Politburo, and the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee, as well as heading two commissariats. Stalin had become a key figure in the party apparatus.

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 69

On May 8, 18-23, 1919 he [Stalin] attended the 8th Congress of the party was elected to the two new bodies–the Politburo (henceforth the central organ of power) and the Orgburo, which at this time was supposed to be a subcommittee of the Central Committee concerned with party organization. When it was suggested (at the 11th Party Congress in 1922) that no one could carry out all Stalin’s party responsibilities and at the same time administer two People’s Commissariats, Lenin replied that no one could name another suitable candidate for the high political responsibilities of the Nationalities Commissariat ‘other than Comrade Stalin’ and, ‘the same applied to the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate. A gigantic job…you have to have at the head of it a man with authority.’ This shows how Lenin now judged Stalin, and the extent to which the latter’s reputation had grown, regardless of particular errors and insubordinations.

Conquest, Robert. Stalin: Breaker of Nations. New York, New York: Viking, 1991, p. 91

When at the Eleventh Party Congress Preobrazhensky listed all of Stalin’s duties and questioned whether it was possible for one man to handle this vast amount of work on the Politburo, the Orgburo, two commissariats, and a dozen subcommittees of the Central Committee, Lenin immediately spoke up in Stalin’s defense, calling him irreplaceable as commissar of nationalities and adding: “The same thing applies to the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate. This is a vast business; but to be able to handle investigations we must have at the head of it a man who enjoys high prestige.”…

Nekrich and Heller. Utopia in Power. New York: Summit Books, c1986, p. 162

At the 11th Congress in 1922 one prominent Bolshevik, Preobrazhensky, would note with astonishment the vast authority which Lenin had concentrated in Koba’s hands. “Take Stalin, for instance…. Is it conceivable that one man can take responsibility for the work of two commissariats, while simultaneously working in the Politburo, the Orgbureau, and a dozen commissions?” But Lenin would not surrender his favorite: “We need a man whom any representative of any national group can approach, a man to whom he can speak in detail. Where can we find such a man? I don’t think Comrade Preobrazhensky could name

any candidate other than Comrade Stalin….

Radzinsky, Edvard. Stalin. New York: Doubleday, c1996, p. 163

The conventional image of Stalin’s ascent to supreme power does not convince. He did not really spend most of his time in offices in the Civil War period and consolidate his position as the pre-eminent bureaucrat of the Soviet state. Certainly he held membership in the Party Central Committee; he was also People’s Commissar for Nationalities’ Affairs. In neither role were his responsibilities restricted to mere administration. As the complications of public affairs increased, he was given further high postings. He chaired the commission drafting the RSFSR Constitution. He became the leading political commissar on a succession of military fronts in 1918-19. He was regularly involved in decisions on relations with Britain, Germany, Turkey, and other powers; and he dealt with plans for the establishment of new Soviet republics in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. He conducted the inquiry into the Red Army’s collapse at Perm. When the Party Central Committee set up its own inner subcommittees in 1919, he was chosen for both the Political Bureau (Politburo) and the Organizational Bureau (or Orgburo). He was asked to head the Workers’ and Peasants’ inspectorate at its creation in February 1920.

Service, Robert. Stalin. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2005, p. 173

LENIN WAS CLOSE TO STALIN AND MADE HIM HIGHER THAN BUKHARIN

Lenin’s relations with Stalin were close, but they were mainly businesslike. He elevated Stalin far higher than Bukharin! And he didn’t simply elevate him but made him his mainstay in the Central Committee. He trusted him.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 116

To this day I recall the first party congress in Petrograd in April, after the February Revolution, when Rykov expressed his rightist sentiments. Kamenev, too, showed this true colors. Zinoviev was still considered to be close to Lenin. Before the elections of members to the Central Committee, Lenin spoke for Stalin’s candidacy. He said Stalin had to be in the Central Committee without fail. He spoke up for Stalin in particular, saying he was such a fine party member, such a commanding figure, and you could assign him any task. He was the most trustworthy in adhering to the party line. That’s the sort of speech it was.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 137

STALIN MOST QUALIFIED SUCCESSOR TO LENIN

Stalin had reasons for thinking himself Lenin’s most loyal disciple and natural heir, in spite of that “testament.” He had been a Bolshevik 20 years, a member of Lenin’s central committees for 10 years, and had served directly under Lenin for six stormy years of revolution. He could easily consider that last conflict as a misunderstanding due to Lenin’s illness, which could have been cleared up if Lenin had recovered. All the other leaders had had worse clashes. Trotsky had opposed Lenin for years and only joined him at the moment of revolution. Zinoviev and Kamenev had been traitors in the very hour of the uprising, opposing it and giving its details in an opposition newspaper. Lenin had forgiven them all. Compared with their sins against Lenin, Stalin’s may well have seemed to him trivial.

Strong, Anna Louise. The Stalin Era. New York: Mainstream, 1956, p. 18

Stalin, whose personality is without any Napoleonic trait, was nevertheless the man who closed the revolutionary epoch and directed the rebuilding of the country. His enemies accuse him of having betrayed the revolution, which is definitely unjust.

Ludwig, Emil, Stalin. New York, New York: G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1942, p. 49

…Stalin achieved colossal results [at the 14th Party Congress]. If not for him, the cadres would not have pulled together. The Bolshevik cadres would not simply obey orders at the wave of a wand. They had to be convinced. The same applied to the old Bolsheviks. Habitually they deferred to no authority or command. They regarded themselves as the equal of an ideological leader…. In 1924 discussion against Trotsky was proceeding full tilt.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 135

Stalin used to say that if Lenin were alive today, surely he would speak differently–there is no doubt about that. He would surely think up something that has not yet occurred to us. But the fact that Stalin was his successor was very fortunate. Very fortunate indeed.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 155

After Lenin, Stalin was the strongest politician. Lenin considered him the most reliable, the one whom you could count upon.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 156

You can’t compare me with him [Stalin]. After Lenin, no one person, not me, or Kalinin, or Dzerzhinsky, or anyone else could manage to do even a tenth of what Stalin accomplished. That’s a fact. I criticize Stalin on certain questions of a quite significant theoretical character, but as a political leader he fulfilled a role which no one else could undertake.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 181

Stalin! The more they assail him, the higher he rises. A struggle is going on. They fail to see the greatness in Stalin. After Lenin there was no more persevering, more talented, greater man than Stalin! After the death of Lenin, no one understood the situation better than Stalin…. Stalin fulfilled his role, an exceptionally important, very difficult role.

Let us assume he made mistakes. But name someone who made fewer mistakes. Of all the people involved in historic events, who held the most correct position? Given all the shortcomings of the leadership of that time, he alone coped with the task then confronting the country….

Despite Stalin’s mistakes, I see in him a great, an indispensable man! In his time there was no equal!

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 183

However, if we wish to determine what Stalin really meant in the history of Communism, then he must for the present be regarded as being, next to Lenin, the most grandiose figure. He did not substantially develop the ideas of Communism, but he championed them and brought them to realization in a society and a state. He did not construct an ideal society…but he transformed backward Russia into an industrial power….

Viewed from the standpoint of success and political adroitness, Stalin is hardly surpassed by any statesman of his time.

Djilas, Milovan. Conversations with Stalin. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962, p. 190

Stalin–“rude,”–sometimes bureaucratic and limited as a Marxist theorist–had a realistic plan for the construction of socialism, and he approached the task with determination, courage, and skill. For all his faults he was the best of the Party leaders available. And this was the opinion of the majority of the Party. Stalin’s report and reply to the discussion at the Thirteenth Congress in 1924 show that he had the Party’s confidence.

Cameron, Kenneth Neill. Stalin, Man of Contradiction. Toronto: NC Press, c1987, p. 52

Certainly before 1921 he showed no pretension to the leadership, and was content to serve. He was proud, sensitive, but not personally ambitious. After removal of Lenin he, like many others, must have wondered about the future of the party. Of the most prominent members Trotsky, towards whom he felt strong antipathy, would endanger unity and the others were not remotely of his caliber. Thus it would seem that during 1922 or 1923 Stalin began to consider seriously that in the interests of the party and communist Russia he would have to take over the leadership, and once having reached this decision he pursued his goal quietly and implacably.

Grey, Ian. Stalin, Man of History. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979, p. 194

He [Stalin] cast himself in the role of leader because none of the other party leaders was remotely capable of assuming it, and because he had developed a burning sense of his mission to lead Russia.

Grey, Ian. Stalin, Man of History. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979, p. 222

At every stage of his career he had grown in stature, showing the confidence and ability to meet greater challenges. He possessed a natural authority, an inner strength and courage. He was not overwhelmed by the responsibilities that now lay upon him as sole ruler over a nation of 200 million people, and at a time when its survival was threatened. He did not play safe, evading dangers which might lead to destruction; on the contrary, although cautious by nature, he pursued his objectives with an implacable single-mindedness, undeterred by risk….

Grey, Ian. Stalin, Man of History. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979, p. 235

My father said that an attentive reading of Lenin’s “Political Testament” shows that he saw nobody but Stalin as fit to succeed him.

Beria, Sergo. Beria, My Father: Inside Stalin’s Kremlin. London: Duckworth, 2001, p. 136

Stalin did not rise to supreme power exclusively by means of the levers of bureaucratic manipulation. Certainly he had an advantage inasmuch as he could replace local party secretaries with persons of his choosing. It is also true that the regime in the party allowed him to control debates in the Central Committee and at Party Congresses. But such assets would have been useless to him if he had not been able to convince the Central Committee and the Party Congress that he was a suitable politician for them to follow. Not only as an administrator but also as a leader,in thought and action,he seemed to fit these requirements better than anyone else.

Service, Robert. Stalin. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2005, p. 246

STALIN WORKED HIS WAY TO THE TOP BY EARNING IT

CHUEV: And how did Stalin rise so high?

MOLOTOV: Thank God. It was the whole story of his life, the Revolution, the Civil War…. Of course, he deserved it….

How did he work his way up? Look, he wrote a very good book on the national question…. He edited the first issue of Pravda.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 165

Stalin will be rehabilitated, needless to say.

Stalin had an astounding capacity for work…. I know this for a fact.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 179

Stalin’s usual routine is to work hard for about a week or longer, then go to the dacha for two or three days to rest. He has few relaxations, but he likes opera and ballet, and attends the Bolshoi Theatre often; sometimes a movie catches his fancy, and he saw Chapayev, a film of the civil wars, four times. He reads a great deal, and plays chess occasionally. He smokes incessantly, and always a pipe; the gossip in Moscow is that he likes Edgeworth tobacco, but is a little hesitant to smoke publicly this non-Soviet product. At dinner he keeps his pipe lit next to his plate, puffs between courses….

Gunther, John. Inside Europe. New York, London: Harper & Brothers, c1940, p. 532

STALIN WAS THE BEST MAN TO REPLACE LENIN

CHUEV: They say that Stalin replaced the Central Committee with a bureaucratic apparatus, and that after Lenin’s death he won power with the help of this apparatus.

MOLOTOV: But who could have led better?

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 166

Whoever will read this book, will think that I am a die-hard Stalinist. I do not absolve Stalin of everything, but I know his character and I also know the circumstances and the bunch of opportunists that were surrounding him in the Politburo. History now has shown us the conditions under which Stalin had to work, think, and lead our country then, during the hectic events, enemies internally and externally doing everything possible to steer the country away from the socialist path…. Could Stalin have known everything that was going on inside the country?

Rybin, Aleksei. Next to Stalin: Notes of a Bodyguard. Toronto: Northstar Compass Journal, 1996, p. 107

LENIN CHOSE STALIN TO LEAD THE BATTLE AGAINST FACTIONS

…Under Lenin there were so many disagreements, so many opposition groups of every conceivable stripe. Lenin regarded this as very dangerous and demanded resolute struggle against it. But he could not take the lead in the struggle against the opposition or against disagreements. Someone had to remain untainted by all repression. So Stalin took the lead, assuming the burden of responsibility in surmounting the vast majority of these difficulties. In my opinion he generally coped with this responsibility correctly. All of us supported him in this. I was one of his chief supporters. I have no regrets over it.

Chuev, Feliks. Molotov Remembers. Chicago: I. R. Dee, 1993, p. 259

STALIN WAS NOT GRASPING FOR POWER BUT WAS GIVEN IT BY LENIN

Although it a usually assumed that Stalin was covertly grasping at positions of power and influence, the fact is that he was promoted mainly on the initiative of Lenin. Once appointed to his various offices he was prompt to exercise the authority necessary to carry out the work.

Grey, Ian. Stalin, Man of History. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979, p. 162

It was at Lenin’s suggestion that Stalin was named commissar of nationalities and commissar of state control, and later commissar of the Workers’ and Peasants Inspection (or Rabkrin, to use the Soviet acronym).

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 63

Stalin, in truth, did not look to be a formidable competitor for power. He had no gift of speech as Trotsky had. He was not an imposing figure. He wore an old khaki tunic with a button missing. He never went to the cleaners. His black hair was uncouth; his thick mustache dropped. He did not have his own automobile as Trotsky had. He was still smart at raiding banks and confiscating money for the Party, but money did not find its way into his pocket. He never showed off in any way. His face was a mask; it looked stupid and narrow-minded but benevolent.

Graham, Stephen. Stalin. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press, 1970, p. 42

After the conquest of power, Stalin began to feel more sure of himself, remaining, however, a figure of the second rank. I soon noticed that Lenin was “advancing” Stalin, valuing in him his firmness, grit, stubbornness, and to a certain extent his slyness, as attributes necessary in the struggle.

Trotsky , Leon , Stalin. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1941, p. 243

LENIN PROPOSED THAT STALIN BE TRANSFERRED FROM GEN. SEC. NOT REMOVED

Lenin proposed in his letter that Stalin be removed from his post as general secretary but did not question the possibility and necessity of keeping Stalin in the leadership. That is why the word “transfer” was used, rather than “remove”. Lenin did not propose any specific person to replace Stalin as general secretary.

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 82

TROTSKY REFUSES TO TAKE A LEADING ROLE WHILE LENIN IS INCAPACITATED

The 12th Party Congress was to be held at the end of April 1923. Lenin was recovering with difficulty from the effects of his third stroke, and it was obvious that he would not be able to take part in the work of the congress. The question arose as to who would give the report in the name of the Central Committee. The most authoritative figure in the Central Committee was still Trotsky. Therefore, it was completely natural that at a meeting of the Politburo Stalin proposed that Trotsky prepare the report. Stalin was supported by Kalinin, Rykov, and even Kamenev. But Trotsky again declined, falling into confused rationalizations to the effect that “the party will be ill at ease if any one of us should attempt, as it were personally, to take the place of the sick Lenin.” Trotsky proposed instead that the Congress proceed without a main political report. This was an absurd proposal, and was, of course, voted down. At one of the next meetings of the Politburo a decision was made– to assign Zinoviev, who had just returned from vacation, to prepare the political report….

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 113

If Trotsky was so sure that he was Lenin’s desired successor; if Trotsky saw that Lenin was not simply ill but paralyzed and unable to speak and write; if Trotsky also saw that Zinoviev and Stalin aspired to Lenin’s place in the party and considered this dangerous to the party; then it is quite impossible to consider his conduct in March and April 1923 correct for a political person.

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 115

In the struggle within the Politburo in the spring of 1923 (a struggle imperceptible to the outside observer) Trotsky displayed complete passivity and in so doing condemned himself to defeat.

Medvedev, Roy. Let History Judge. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, p. 116

And when the last crisis came, when Lenin fell sick and was compelled to withdrawal from the Government, he turned again to Trotsky and asked him to take his place as President of the Soviet of People’s Commissars and of the Council of Labor and Defense. And, moreover, when Trotsky declined, Lenin did not turn to any other strong man; he passed over the heads of those who might conceivably imagine themselves to be rivals of Trotsky, and divided the position among three men who are obviously not leaders [Rykov, Tzuryupov, and Kamenev].

Eastman, Max. Since Lenin Died. Westport, Connecticutt: Hyperion Press. 1973, p. 16

The next Party Congress,the 12th,was scheduled for April 1923. The Politburo aimed to show that the regime could function effectively in Lenin’s absence. Trotsky was offered the honor of delivering the political report on behalf of the Central Committee, but refused.

Service, Robert. Stalin. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2005, p. 212

[Nevertheless Zinoviev was foolhardy enough to insist on taking Lenin’s place at the Twelfth Congress and assumed the role of Lenin’s successor by delivering the Political Report at its opening session. During the preparations for the Congress, with Lenin ill and unable to attend,] the most ticklish question was who should deliver this keynote address, which since the founding of the Party had always been Lenin’s prerogative. When the subject was broached in the Politburo, Stalin was the first to say, “The Political Report will of course be made by Comrade Trotsky.”

I did not want that, since it seemed to me equivalent to announcing my candidacy for the role of Lenin’s successor at a time when Lenin was fighting a grave illness. I replied approximately as follows: “This is an interim. Let us hope that Lenin will soon get well. In the meantime the report should be made, in keeping with his office, by the General Secretary….

I continued to insist on Stalin making the report.

“Under no circumstances,” he replied with demonstrative modesty. “The Party will not understand it. The report must be made by the most popular member of the Central Committee.

Trotsky , Leon , Stalin. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1941, p. 366

STALIN EFFECTIVELY ROSE IN THE PARTY

In six years (from 1923 to 1929) Stalin outmaneuvered a series of opponents; first, in alliance with all the rest of his colleagues, he opposed and demoted Trotsky. Then, in alliance with the Bukharin-Rykov ‘Right’ he defeated the Zinoviev-Kamenev ‘Left’ bloc, and then a new alliance between these and the Trotskyites. And finally he and his own following attacked their heretofore allies, the ‘Rightists’.

Bukharin was later to criticize Stalin as a master of ‘dosing’–of getting his way in gradual doses. That this was supposed to be a damaging point is a measure of Bukharin’s (and others’) comparative incompetence.

Conquest, Robert. Stalin: Breaker of Nations. New York, New York: Viking, 1991, p. 131

TROTSKY REFUSES TO TAKE LEADING POSITIONS OFFERED BY LENIN AND STALIN

On Sept. 11, 1922, Lenin addressed to Stalin a note for the Politburo in which he suggested that in view of Rykov’s imminent departure for a vacation and Tsiurupa’s inability to handle the whole load by himself, two new deputy chairman be appointed, one to help oversee the Council of People’s Commissars, the other, the Council of Labor and Defense: both were to work under close supervision of the Politburo and himself. For the posts he suggested Trotsky and Kamenev. A great deal has been made by Trotsky’s friends and enemies alike of this bid: some of the former went so far as to claim that Lenin chose him as his successor. (Max Eastman, for example, wrote not long afterward that Lenin had asked Trotsky to “become the head of the Soviet government, and thus of the revolutionary movement of the world.”) The reality was more prosaic. According to Lenin’s sister, the offer was made for “diplomatic reasons,” that is, to smooth Trotsky’s ruffled feathers; in fact, it was because it was so insignificant that Trotsky would have none of it. When the Politburo voted on Lenin’s motion, Stalin and Rykov wrote down “Yes,” Kamenev and Tomsky abstained, Kalinin stated “No objections,” while Trotsky wrote “Categorically refuse.” Trotsky explained to Stalin why he could not accept the offer. He had previously criticized the institution of zamy on grounds of substance. Now he raised additional objections on grounds of procedure: the offer had not been discussed either at the Politburo or at the Plenum, and, in any event, he was about to leave on a four-week vacation. But his true reason very likely was the demeaning nature of the proposal: he was to be one of four deputies–one of them not even a Politburo member–without clearly defined responsibilities: a meaningless “deputy as such.” Acceptance would have humiliated him; refusal, however, handed his enemies deadly ammunition. For it was quite unprecedented for a high Soviet official “categorically” to refuse an assignment.

Pipes, Richard. Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1993, p. 466

As reward for Trotsky’s collaboration, Stalin in January 1923 once again offered him the post of a zam in charge of either the VSNKh or the Gosplan. Trotsky again refused.

Pipes, Richard. Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1993, p. 470

On his [Trotsky] new platform he acquired some support, especially from the so-called “Group of Forty-Six,” members who shared his views and sent a letter to this effect to the Central Committee. The directing organs of the party, however, had a ready answer: the letter constituted a “platform” that could lead to the creation of an illegal faction. In a lengthy rebuttal, it took Trotsky to task [by stating],

“Two or three years ago, when Comrade Trotsky began his “economic” pronouncements against the majority of the Central Committee, Lenin himself explained to him dozens of times that economic questions belong to a category that precludes quick successes, that requires years and years of patient and persistent work to achieve serious results…. To secure correct leadership of the country’s economic life from a single center and to introduce into it the maximum of planning, the Central Committee in the summer of 1923 reorganized the Council of Labor and Defense, introducing into it personally a number of the leading economic workers of the republic. In that number, the Central Committee elected also Comrade Trotsky. But Comrade Trotsky did not consider making an appearance at meetings of the Council of Labor and Defense, just as for many years he had failed to attend meetings of the Sovnarkom and rejected the proposal of Comrade Lenin to be one of the deputies of the Sovnarkom Chairman…. At the basis of Comrade Trotsky’s discontent, of his whole irritation, of all his assaults over the years against the Central Committee, of his decision to rock the party, lies the circumstance that Comrade Trotsky wants the Central Committee to have him and Comrade Kolegaev take charge of our economic life. Comrade Lenin had long fought against such an appointment, and we believe he was entirely correct…. Comrade Trotsky is a member of the Sovnarkom and of the reorganized Council of Labor and Defense. He has been offered by Comrade Lenin the post of deputy of Sovnarkom chairman. Had he wanted, in all these positions Comrade Trotsky could have demonstrated to the entire party in fact, indeed, that he can be entrusted with that de facto unlimited authority in the field of economic and military affairs for which he strives. But Comrade Trotsky preferred a different method of action, one which, in our opinion, is incompatible with the duties of a party member. He has attended not a single meeting of the Sovnarkom either under Comrade Lenin or after Comrade Lenin’s retirement from work. He has attended not a single meeting of the Council of Labor and Defense, whether old or reorganized. He has not moved once either in the Sovnarkom, or in the Council of Labor and Defense, or in the Gosplan any proposals concerning economic, financial, budgetary, and so forth, questions. He has categorically refused to be Comrade Lenin’s deputy: this he apparently considers below his dignity. He acts according to the formula “All or Nothing.” In fact, Comrade Trotsky has assumed toward the party the attitude that it either must grant him dictatorial powers in the economic and military spheres, or else he will, in effect, refuse to work in the economic realm, reserving himself only the right to engage in systematic disorganization of the Central Committee in its difficult day-to-day work.”

Pipes, Richard. Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1993, p. 484

After the seizure of power, I tried to stay out of the government, and offered to undertake the direction of the press.

…One thing coincided with the other, and this only added to my desire to retire behind the scenes for a while. Lenin would not hear of it, however. He insisted that I take over the commissariat of the interior, saying that the most important task at the moment was to fight off a counter-revolution. I objected, and brought up, among other arguments, the question of nationality. Was it worthwhile to put into our enemies hands such an additional weapon as my Jewish origin?

Lenin almost lost his temper. “We are having a great international revolution. Of what importance are such trifles?”

If, in 1917 and later, I occasionally pointed to my Jewish origin as an argument against some appointment, it was simply because of political considerations.

… I, likewise with reluctance, consented. And thus, at the instigation of Sverdlov, I came to head the Soviet diplomacy for a quarter of a year.

Trotsky, Leon. My Life. Gloucester, Massachusetts: P. Smith, 1970, p. 340-341

When I was declining the commissariat of home affairs on the second day after the revolution, I brought up, among other things, the question of race [Jewish].

Trotsky, Leon. My Life. Gloucester, Massachusetts: P. Smith, 1970, p. 360

Stalin suggested that Trotsky should present the main report at the 12th Congress but Trotsky sensibly refused, rightly believing that this would be taken as an assumption of Lenin’s mantle.

Conquest, Robert. Stalin: Breaker of Nations. New York, New York: Viking, 1991, p. 106

There was, however, no intrigue to get the post [General Secretary of the CPSU]. Trotsky did not want it.

Graham, Stephen. Stalin. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press, 1970, p. 78

Later all on, judging from some accidental and quite erroneous indications, he [Lenin] concluded I was being too dilatory in the matter of an armed uprising, and this suspicion was reflected in several of his letters during October…. The next day, at the meeting of the Central Committee of the party, he proposed that I be elected chairman of the Soviet of People’s Commissaries. I sprang to my feet, protesting–the proposal seemed to me so unexpected and inappropriate. “Why not?” Lenin insisted. “You were at the head of the Petrograd Soviet that seized the power.” I moved to reject his proposal, without debating it. The motion was carried.

Trotsky, Leon. My Life. Gloucester, Massachusetts: P. Smith, 1970, p. 339

I felt the mechanics of power as an inescapable burden, rather than as a spiritual satisfaction.

Trotsky, Leon. My Life. Gloucester, Massachusetts: P. Smith, 1970, p. 582

[In the reply of the Politburo to Trotsky’s letter of October 1923 to the Central Committee is the following:]

“Trotsky is a member of the Soviet of People’s Commissars, a member of the Soviet of Labor and Defense; Lenin offered him the post of vice-president of the Soviet of People’s Commissars. In all these positions Trotsky might, if he wished to, demonstrate in action, working before the eyes of the whole party, that the party might trust him with those practically unlimited powers in the sphere of industry and military affairs towards which he strives. But Trotsky preferred another method of action…. He never attended a meeting of the Soviet of People’s Commissars, neither under Lenin, nor after his withdrawal. He never attended a meeting of the Soviet of Labor and Defense, neither before nor after its reorganization….

Trotsky categorically declined the position of substitute for Lenin. That evidently he considers beneath his dignity. He conducts himself according to the formula, ‘All or nothing.'”

Eastman, Max. Since Lenin Died. Westport, Connecticutt: Hyperion Press. 1973, p. 144-145

Stalin was perfectly well aware that relations between Lenin and Trotsky had recently become increasingly close. He had not been much concerned about this during 1922, for the two leaders, while never in conflict on points of principle [That is false–Ed], had perpetually engaged in skirmishes on current questions. This did not prevent Lenin from suggesting to Trotsky that he should become his deputy, but Trotsky had refused, and on this occasion Stalin had succeeded, not without a certain malicious satisfaction, in getting the Politburo to censure Trotsky for failure of duty.

Lewin, Moshe. Lenin’s Last Struggle. New York: Pantheon Books. C1968, p. 71

When Trotsky heard that, despite the considerable administrative load he was already bearing, the Politburo wanted to put him in charge of the state treasury under the Finance Commissariat, he refused, sending a written explanation. Lenin reacted with a note to the Politburo: “Trotsky’s letter is unclear. If he is refusing, a decision of the Politburo is required. I am for not accepting his resignation.

Volkogonov, Dmitrii. Lenin: A New Biography. New York: Free Press, 1994, p. 257

Throughout the summer of 1922 the disagreements in the Politburo over domestic issues dragged on inconclusively. The dissension between Lenin and Trotsky persisted. On 11 September from his retreat in Gorky, outside Moscow, Lenin made contact with Stalin and asked him to place before the Politburo once again and with the utmost urgency a motion proposing Trotsky’s appointment as deputy Premier. Stalin communicated the motion by telephone to those members and alternate members of the Politburo who were present in Moscow. He himself and Rykov voted for the appointment; Kalinin declared that he had no objections, while Tomsky and Kamenev abstained. No one voted against. Trotsky once again refused the post. Since Lenin had insisted that the appointment was urgent because Rykov was about to take leave, Trotsky replied that he, too, was on the point of taking his holiday and that his hands were, anyhow, full of work for the forthcoming congress of the International. These were irrelevant excuses, because Lenin had not intended the appointment to be only a stopgap for the holiday season. Without waiting for the Politburo’s decision, Trotsky left Moscow. On 14 September the Politburo met and Stalin put before it a resolution which was highly damaging to Trotsky; it censured him in effect for dereliction of duty. The circumstances of the case indicate that Lenin must have prompted Stalin to frame this resolution or that Stalin at least had his consent for it.

Deutscher, Isaac. The Prophet Unarmed. London, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1959, p. 65

Now as before the economic administration bungled and muddled. Nothing had been done to make Gosplan the guiding center of the economy. The Politburo set up a number of committees to investigate symptoms of the crisis instead of going to its root. Trotsky himself had been invited to serve on a committee which was to inquire into prices; but he refused to do so. He had no wish, he declared, to participate in an activity designed to dodge issues and to postpone decisions.

…Other collisions developed when the triumvirs proposed changes in the Military Revolutionary Council over which Trotsky presided. Zinoviev was bent on introducing into that Council either Stalin himself or at least Voroshilov and Lashevich…. Trotsky, hurt and indignant, declared that he was resigning in protest from every office he held, the Commissariat of War, the Military Revolutionary Council, the Politburo, and the Central Committee. He asked to be sent abroad “as a soldier of the revolution” to help the German Communist party to prepare its revolution.

Deutscher, Isaac. The Prophet Unarmed. London, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1959, p. 111

In the summer of 1922, when he [Trotsky] refused to accept the office of Vice-Premiere under Lenin and, incurring the Politburo’s censure, went on leave, he devoted the better part of his holiday to literary criticism.

Deutscher, Isaac. The Prophet Unarmed. London, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1959, p. 164

Still defeated the Left Opposition, not just because his policies proved to be more attractive for the broad masses of the population or for a considerable section of the Party cadres, but to a very large extent because of the plain fact that in the first, decisive stages of the struggle for power, Trotsky simply opted out.

Medvedev, Roy. On Stalin and Stalinism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979, p. 46

Searching for an ally, Lenin turned to Trotsky. Twice in the course of 1922 he had urged Trotsky to accept the post of a deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, and twice Trotsky had refused, failing to see the opportunity Lenin was offering him to establish his political position as first among his deputies.

Bullock, Alan. Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives. New York: Knopf, 1992, p. 119

Trotsky was already War Minister, and Lenin and the Central Committee had tried several times to make him also a deputy chairman of the Council of Commissars. Trotsky always refused out of pride since there were already several deputy chairmen.

Ulam, Adam. Stalin; The Man and his Era. New York: Viking Press, 1973, p. 226

The reply of the Political Bureau, led by Stalin, Kamenev, and Zinoviev, was that Trotsky could have had, as a member of the government, and in the capacity of vice-premier which Lenin had offered him, every opportunity “if you wished to, to demonstrate in action that the party might trust him with those practically unlimited powers in the sphere of industry and military affairs toward which he strives. But Trotsky preferred another method of action…. He never attended a meeting of the council of people’s commissars, either under Lenin or after his withdrawal. He never attended a meeting of the council of labor and defense, either before or after its reorganization….

The Politburo said, “Trotsky categorically declined the position of substitute for Lenin. That evidently he considers beneath his dignity. He conducts himself according to the formula: ‘All or nothing.'”

Levine, Isaac Don. Stalin. New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, c1931, p. 229

[At the 13th Conference of the Party in January 1924 Stalin stated] Let me recall two facts so that you may be able to judge for yourselves. First, the incident which occurred at the September plenum of the Central Committee when, in reply to the remark by Central Committee member Komarov that Central Committee members cannot refuse to carry out Central Committee decisions, Trotsky jumped up and left the meeting. You will recall that the Central Committee plenum sent a “delegation” to Trotsky with the request that he return to the meeting. You will recall that Trotsky refused to comply with this request of the plenum, thereby demonstrating that he had not the slightest respect for this Central Committee.

There is also the other fact, that Trotsky definitely refuses to work in the central Soviet bodies, in the Council of Labor and Defense and the Council of People’s Commissars, despite the twice-adopted Central Committee decision that he at last take up his duties in the Soviet bodies. You know that Trotsky has not as much as moved a finger to carry out this Central Committee decision.

Stalin, Joseph. Works. Moscow: Foreign Languages Pub. House, 1952, Vol. 6, p. 39

The same day that Lenin sent Stalin the demand for an apology, 5 March 1923, he also sent Trotsky a note asking him to take over the ‘Georgian affair’, providing him with the dictations of 30-1 December on the problem of minority nationalism. Trotsky declined this commission, thus missing a fine opportunity to deal Stalin a serious blow. His excuse was illness, and it is true that he intermittently ran a debilitating fever during most of the 1920s. But he was not too ill to report to the Congress of April 1923 on a different topic, and he at least could have read the dictations to the Congress, thus presenting himself as a close ally of Lenin. One explanation of Trotsky’s self-defeating decision might be the excessive self-confidence that Lenin had noted in his dictation. Trotsky perhaps could not conceive that he would have to exert himself to be recognized as the principal successor to Lenin. Another explanation might be that Trotsky was not interested in belaboring Russian chauvinism and defending minority nationalism….

McNeal, Robert, Stalin: Man and Ruler. New York: New York University Press, 1988, p. 78

Trotsky’s rejection of Lenin’s request [to take over the Georgian affair] was at least as serious an example of disloyalty to the founder as Stalin’s insults to Krupskaia, but the latest decline in Lenin’s health closed that issue.

McNeal, Robert, Stalin: Man and Ruler. New York: New York University Press, 1988, p. 78

[Footnote]: In his response to Lenin’s repeated offer [of being a deputy chairman of sovnarkom] Trotsky said that he would accept the job if the Central Committee ordered him to, but that this would be ‘profoundly irrational’ and contrary to his administrative ‘plans and intentions’. This brusqueness was far from the impression of friendly relations that he described in his book My Life. This memoir was even more inaccurate in stating that Lenin had not previously offered him the position.

McNeal, Robert, Stalin: Man and Ruler. New York: New York University Press, 1988, p. 345

LENIN CHOSE STALIN AS GEN. SEC.

At this stage his power was already formidable. Still more was to accrue to him from his appointment, on April 3, 1922, to the post of General Secretary of the Central Committee. The 11th Congress of the party had just elected a new and enlarged Central Committee and again modified the statutes. The leading bodies of the party were now top-heavy; and a new office, that of the General Secretary, was created, which was to co-ordinate the work of their many growing and overlapping branches. It was on that occasion, Trotsky alleges, that Lenin aired, in the inner circle of his associates, his misgivings about Stalin’s candidature: ‘This cook can only serve peppery dishes.’ But his doubts were, at any rate, not grave; and he himself in the end sponsored the candidature of the ‘cook’. Molotov and Kuibyshev were appointed Stalin’s assistants, the former having already been one of the secretaries of the party.

Deutscher, Isaac. Stalin; A Political Biography. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1967, p. 232

Stalin did not make himself general secretary. Lenin did. Lenin had been his mentor, protector, and constant model.

Nekrich and Heller. Utopia in Power. New York: Summit Books, c1986, p. 162

In regard to Stalin three facts can hardly be controverted. First, in January, 1912, at the Prague Conference of the Communist Party, Lenin proposed the election of Stalin to the Central Committee of the Party and placed him at the head of the “Russian Bureau” in charge of all Communist activities on Russian soil. Second, when the Politburo was first formed by Lenin in May, 1917, Stalin was chosen by Lenin to be a member and has been reelected to it at every Party Congress since. Third, when Lenin felt death’s hand upon his shoulder early in 1922, he named Stalin General Secretary of the Communist Party, which he knew and all the Communists knew was the key position in the Party, as Stalin later proved by using it to make himself Lenin’s successor.

Duranty, Walter. Stalin & Co. New York: W. Sloane Associates, 1949, p. 66

A ‘party school’ had been held by Lenin in 1911 at Longjumeau outside Paris, and Dzhughashvili was one of the individuals he had wanted to have with him. ‘People like him’, he [Lenin] said to the Georgian Menshevik Uratadze, ‘are exactly what I need.’

Service, Robert. Stalin. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2005, p. 82

Lenin and his entourage therefore decided to reinforce the Secretariat in two ways–by establishing the office of General Secretary, with the other two members acting as his assistants rather than equal colleagues, and by selecting for the position of General Secretary the man most capable of strong-arm work, Joseph Stalin.

Trotsky, Leon, Stalin. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1941, p. 351

STALIN & TROTSKY EACH TRY TO GET THE OTHER TO GIVE THE KEY SPEECH WHEN LENIN LEFT

At the session of the Politburo which discussed new arrangements for the Congress [the 12th Party Congress], the first Congress in the whole history of the party that was not to be guided by Lenin, Stalin proposed that, in place of Lenin, Trotsky should address the Congress on behalf of the Central Committee, as its chief rapporteur…. Trotsky refused to act in Lenin’s customary role, lest people should think that he was advancing his claim to the leadership even before Lenin was dead. His apprehension was certainly genuine. But then he went on to propose that Stalin, as General Secretary, should ex officio act in place of Lenin. The latter, too, was cautious enough to refuse. In the end Zinoviev accepted the risky honor.

Deutscher, Isaac. Stalin; A Political Biography. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1967, p. 253

It was the early weeks of 1923, and the 12th Congress was drawing near. There remained little hope that Lenin could take part in it. The question of who was to make the principal political report arose. At the meeting of the Politburo, Stalin said, “Trotsky, of course.” He was instantly supported by Kalinin, Rykov, and, obviously against his will, by Kamenev. I objected.

Stalin knew that a storm was menacing him from Lenin’s direction, and tried in every way to ingratiate himself with me. He kept repeating that the political report should be made by the most influential and popular member of the Central Committee after Lenin: i.e., Trotsky, and that the party expected it and would not understand anything else.

Trotsky, Leon. My Life. Gloucester, Massachusetts: P. Smith, 1970, p. 489

The 12th Party Congress was from 17 to 23 April 1923. A major problem arose: Who would present the congress with the Central Committee’s political report, the most important political document of the year? This task had always been Lenin’s. Whoever did it would be considered by the Party to be Lenin’s successor.

At the Politburo meeting Stalin proposed that Trotsky present the report….

With astonishing naivete, Trotsky refused. He didn’t want the Party to think he was usurping the place of a sick Lenin. In his turn, he proposed that Stalin give the report as general secretary of the Central Committee. I can just imagine Zinoviev’s emotions at that moment. But Stalin also refused. He understood perfectly well that the Party would not understand and wouldn’t accept him, for nobody then considered him as one of the top Party bosses. In the end, with Kamenev’s help, Zinoviev was tasked with presenting the report. He was president of the Comintern, and if anyone should temporarily replace the ill Lenin, it was he. Zinoviev gave the political report to the congress in April.

Bazhanov, Boris. Bazhanov and the Damnation of Stalin. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, c1990, p. 30

SOLKOLNIKOV WAS THE ONLY 1926 SPEAKER TO URGE REMOVAL OF STALIN AS GEN. SEC.

I often went to visit Sokolnikov, who had been a lawyer…. After the 13th Party Congress in May 1924, he was named candidate member of the Politburo. At the 1926 congress he took the side of Zinoviev and Kamenev and was the only platform speaker to urge removal of Stalin from the general secretaryship. That cost him his job as peoples’ commissar and his place on the Politburo.

Bazhanov, Boris. Bazhanov and the Damnation of Stalin. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, c1990, p. 86

STALIN REFUSES TO ACCEPT TROTSKY’S RESIGNATION AS WAR COMMISSAR

The triumvirs could not let him go…. Zinoviev replied that he himself, the President of the Communist International, would go to Germany “as a soldier of the revolution” instead of Trotsky. Then Stalin intervened, and with a display of bonhomie and common sense said that the Politburo could not possibly dispense with the services of either of its two most eminent and well-beloved members. Nor could it except Trotsky’s resignation from the Commissariat of War and the Central Committee, which would create a scandal of the first magnitude. As for himself, he, Stalin, would be content to remain excluded from the Military Revolutionary Committee if this could restore harmony. The Politburo accepted Stalin’s “solution”; and Trotsky, feeling the grotesqueness of the situation, left the hall in the middle of the meeting “banging the door behind him.”

Deutscher, Isaac. The Prophet Unarmed. London, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1959, p. 112

TROTSKY WAS FAR TOO UNPOPULAR WITH THE PEASANTS TO TAKE OVER AFTER LENIN

In his preface to the German edition of Serge’s memoirs, Erich Wollenberg [a German revolutionary Communist who moved to the Soviet Union in the early 1920s after the final defeat of insurrection in Germany] rather persuasively disputes Serge’s version of the facts.

“… Within the Party itself there was unquestionably a majority supporting the troika: i.e. the ruling triumvirate composed of Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Stalin. They were regarded in precisely that order of importance, with Stalin in last place.

If there had been some way of changing the Soviet Constitution and carrying out an election, who among Lenin’s followers would have received the most votes? Although the result would be impossible to predict, we can be sure about one thing: in view of the hostility of the peasantry and of the middle-class which in the early 1920s had come to regard Trotsky as an opponent of NEP, an overwhelming majority of those voting in the election would have been against Trotsky.

It is necessary to stress this point unequivocally, since to this day Trotskyists of all kinds, and even experts on Soviet affairs in the Federal Republic and other countries, express the view in conversation, in print, and on television that Trotsky actually had a “real chance” after Lenin’s death.

Medvedev, Roy. On Stalin and Stalinism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979, p. 53

STALIN WORKED VERY HARD IN THE EARLY YEARS TO BUILD THE PARTY

During the years of reaction he [Stalin] was not one of the tens of thousands who deserted the Party, but one of the very few hundreds who, despite everything, remained loyal to it.

Trotsky, Leon, Stalin. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1941, p. 113

Toward the end of February 1917, Stalin, who had returned from abroad, made his home with the same deputies: “He played the leading role in the life of our [Duma] faction and of the newspaper Pravda,” relates Samoilov, “and he attended not only all the conferences, which we arranged in our apartment, but not infrequently, with great risk to himself, visited also the sessions of the Social-Democratic faction, where, upholding our position in arguments against the Mensheviks and on various other questions, he rendered us great service.”

Trotsky, Leon, Stalin. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1941, p. 159

EFFORTS TO PROVE STALIN WAS NOT LEGALLY THE GENERAL SECRETARY ARE BASELESS

One particular point concerning the reconstituted party regime has remained an enigma. Announcements of postcongress plenums in 1922 and after said not only that Stalin was elected a Central Committee secretary, but also that the new Central Committee confirmed him as general secretary. This time there was no reference to such confirmation. From the omission a veteran observer of Soviet politics has inferred that the new Central Committee deprived Stalin of the position of general secretary and all the associated “additional rights” that set him apart from the other Central Committee secretaries. A large interpretation of the history of the Soviet regime in the ensuing years flowed from the hypothesized grave setback of Stalin’s fortunes.

The inference, however, was unfounded. First, general secretary was a special title accorded Stalin as the senior Central Committee secretary, not, technically speaking, an office. The office was that of secretary, as indicated by the fact that both before and after 1934 Stalin signed party decrees “Secretary of the Central Committee.” Secondly, Soviet official sources testify that Stalin did not cease to be general secretary in February 1934 even though the announcement concerning the postcongress plenum made no mention of his having been confirmed as such. Thirdly, the symbolic evidence cited above and the signs of Stalin’s heavy influence in the reshaping of the party regime contradict the notion that his power was reduced by the new Central Committee whose very composition testified to this power.

Tucker, Robert. Stalin in Power: 1929-1941. New York: Norton, 1990, p. 263

TROTSKY TRIES TO MILITARIZE THE TRADE UNIONS

When Stalin requisitioned the grain of the south to feed the hungry population of the north, he had regard neither for the open market of capitalism nor for the principle of the future exchange of goods in communist society. He was doing what any State power would have had to do if it intended to survive, whether that State were a slave, feudal, capitalist, or socialist. The economics of War Communism were the economics of survival, and that they took on extreme forms of centralization of authority, applied measures of confiscation right and left, requisitioned without regard for the economic niceties of the market, is incidental.

At this period Stalin and Trotsky again found themselves in opposite camps. Flushed with enthusiasm for the growing discipline of the Red Army, Trotsky initiated the transformation of its regiments into military Labor Battalions. Again showing his characteristic lack of confidence in the workers, he proposed to militarize labor in industry and make the Trade Unions into governmental institutions which would effect the necessary discipline. He opposed the election of trade union officials and favored their appointment by the Government….

Lenin and Stalin together fought Trotsky’s proposal. They insisted that the Trade Unions be voluntary and democratic, elect their officials, adopt methods of comradely persuasion and eschew the dictatorial practices of the military-minded.

Murphy, John Thomas. Stalin, London, John Lane, 1945, p. 140

This instance [causing a huge eventual loss by refusing to sign the Brest-Litovsk Treaty] is enough to show the Trotsky had no comprehension of political realities. This was made clear again on later occasions. To quote only one instance, after the end of the Civil War Trotsky hit upon the idea of assisting the needed economic reconstruction by not demobilizing the Red Army but converting it into a labor force. He wanted to organize forced labor under military discipline on an altogether unprecedented scale. And this in a country already full of revolutionary anarchy! In his articles he declared that it was a bourgeois prejudice that regarded forced labor as economically inferior to free labor. If Trotsky’s idea had been carried out, in all probability the Bolshevik regime would have been brought down….

Basseches, Nikolaus. Stalin. London, New York: Staples Press, 1952, p. 125

Stalin’s position on this question of labor armies is of importance in a study of his character because it destroys the popular conception of him as a ruthless Dictator and demonstrates that, provided such a course is not detrimental to the well-being of the Soviet state, he is always prepared to deal with a problem from a humanitarian standpoint.

Cole, David M. Josef Stalin; Man of Steel. London, New York: Rich & Cowan, 1942, p. 53

In 1920 a controversy on the trade union question arose in the party. It arose because Trotsky and his followers had proposed that the policy of the period of War Communism be continued in every sphere of economic and Party work, and that the “screw be put on tighter.”

Yaroslavsky, Emelian. Landmarks in the Life of Stalin. Moscow: FLPH, 1940, p. 115

PARTY OUTLAWS FACTIONS AND DEMOTES TROTSKYISTS

At the Tenth Bolshevik Party Congress, in March 1921, the Central Committee headed by Lenin passed a resolution outlawing all “factions” in the party as a menace to the unity of the revolutionary leadership. From now on all party leaders would have to submit to the majority decisions and the majority rule, on penalty of expulsion from the party. The Central Committee specifically warned “Comrade Trotsky” against his “factional activities,” and stated that “enemies of the state,” taking advantage of the confusion caused by his disruptive activities were penetrating the party and calling themselves “Trotskyites.” A number of important Trotskyites and other Left Oppositionists were demoted. Trotsky’s chief military aide, Muralov, was removed as Commander of the strategic Moscow Military Garrison and replaced by the old Bolshevik, Voroshilov.

The following year, in March 1922, Joseph Stalin was elected general secretary of party….

Sayers and Kahn. The Great Conspiracy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1946, p. 196

There was also sharp divergence amongst the delegates to the Tenth Party Congress about the powers and functions of labor unions in the Soviet State. Feelings ran so high and differences of opinions were so violent on both these important questions (the NEP and labor unions) that Lenin was led to make an impassioned plea for Party Unity, which he described as the cardinal and all-essential factor for this and every subsequent Congress to remember and reserve.

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 70

The Tenth Congress further authorized the Central Committee, as supreme permanent organism of the Party, to apply appropriate penalties to all Communists–including members of the Committee itself–guilty of violating party discipline, and especially of creating intra-party factions.

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 70

This incident so alarmed Lenin that he caused the 10th Congress of the CPSU to pass a special resolution against the formation of separate blocks, groups, and factions within the Party. Lenin was of the view that party members were entitled to differ with each other and to resolve their differences by discussion. But once a decision had been arrived at after a thorough discussion, and criticism had been exhausted, unity of will and action of the Party members were necessary, for without this unity a proletarian Party and proletarian discipline were inconceivable. This Trotsky could never understand. Whenever he found himself in a minority he rushed ahead to form a faction within the Party–thus jeopardizing the Party and the Soviet Republic.

Brar, Harpal. Trotskyism or Leninism. 1993, p. 103

When Trotsky asks about the rights of factions, it is not the right of Communist Party members to express their opinion within the Party that he is concerned with. That is not and never has been challenged. What Trotsky means by factions is not minority opinion on one or another issue within the Party, but the right of a group to establish its own leadership, its own connections, its own press within the Party–in short, its right to establish a party within the Party with a view to splitting the Party. That will never be tolerated.

Campbell, J. R. Soviet Policy and Its Critics. London: V. Gollancz, ltd., 1939, p. 187

A Party conference, the first organized by him [Stalin], was held in January 1924. It was unsparing in its condemnation of Trotsky and the opposition, and it decided that the secret resolution [Lenin’s resolution] “on expulsion from the Party for factional activity” should be made public for the first time.

Radzinsky, Edvard. Stalin. New York: Doubleday, c1996, p. 212

LENIN SHUT DOWN FACTIONALISM AND HAD MAJOR PURGE

The controversies engendered by the adoption of the NEP caused Congress X (March, 1921) to order the dissolution of all factional groups and the expulsion from membership, on the order of the Central Committee, of all deemed guilty of reviving factionalism, infringing the rules of discipline, or violating Congress decisions. During 1921 some 170,000 members, about 25% of the total, were expelled in a mass purge which continued throughout 1922. So drastic was this cleansing that Congress XII (April, 1923) was attended by only 408 delegates representing 386,000 members, as compared with 694 and 732,000 in March, 1921. The Congress rejected proposals by Krassin and Radek for large scale concessions to foreign capital, by Bukharin and Sokolnikov for abandoning the State monopoly of foreign trade, and by Trotsky for reversing Lenin’s policy of conciliating the peasantry. In the autumn of 1923 Trotsky issued a “Declaration of the 46 Oppositionists,” criticizing the NEP, predicting a grave economic crisis and demanding full freedom for dissenting groups and factions. Immediately after Congress XI (March, 1922) the Plenum of the Central Committee, on Lenin’s motion, had chosen Stalin as General Secretary of the Committee.

Schuman, Frederick L. Soviet Politics. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1946, p. 198

The 1921 Purge was so severe that the party membership was reduced from 732,000 (at the time of the Tenth Congress in March, 1921) to 532,000 at the Eleventh Congress in March, 1922.

Duranty, Walter. Story of Soviet Russia. Philadelphia, N. Y.: JB Lippincott Co. 1944, p. 71

In March 1921 there was a serious mutiny of sailors of the Kronstadt naval base near Petrograd, previously noted for their ardent radicalism. This was not the doing of the Bolshevik dissenters, but at the party congress of March 1921 Lenin used it as an example of what dissent could lead to thanks to the machinations of the Mensheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries, and imperialists. The Congress passed a resolution forbidding intra-party factions, with a secret article that permitted the Central Committee to discipline, even to expel from the party (that is, remove from political life), any factionalists, including Central Committee members. Those who wish to portray Lenin as a pluralist at heart have observed that this was an exceptional measure during a crisis at the end of a devastating civil war and that it was not intended to be a permanent feature of Bolshevism. But Lenin never suggested in the two years following this resolution that he thought it might be rescinded, even though the crisis had passed.

McNeal, Robert, Stalin: Man and Ruler. New York: New York University Press, 1988, p. 83

LENIN OPPOSED WORKERS’ OPPOSITION AND ANARCHO-SYNDICALISTS